Expansion and Motivation: Frontiers and Borders in the Past and Present of the United States and Russia

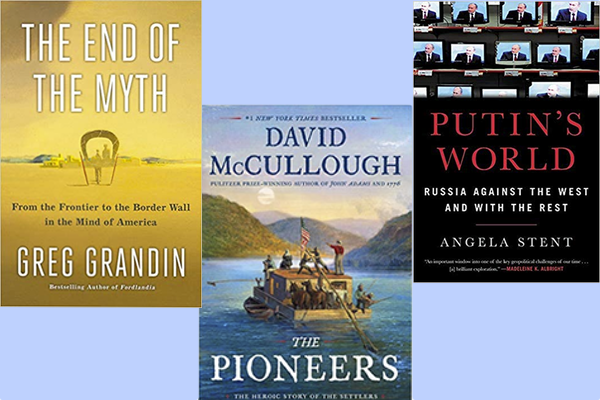

Three new books push us to consider and compare the role of the frontier, or sometimes borders, in the past and present of Russia and the United States. Greg Grandin, The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America (Henry Holt, 2019); and David McCullough, The Pioneers: The Heroic Story of the Settlers Who Brought the American Ideal West (Simon and Schuster, 2019) take virtually diametrically opposed stances on what the frontier and its settlement have meant to America. Grandin argues that expansion provided a “safety valve,” although it did not work well, for release of tension produced by internal difficulties. In his book, expansion across North America and in foreign wars, at a great cost in blood and abandonment of ideals, is at the heart of the American experience. McCullough offers fulsome praise for expansion in the case of Ohio, where he finds that true American ideals were put into practice. Angela Stent, Putin’s World: Russia Against the West and with the Rest (Hachette, 2019) discusses Russia’s past expansion and its relationship with “near abroad” neighbors; she finds, no surprise, that the issue bears gravely on the question of what Russia wants today.

The history of both Russia and America can be written around the issue of expansion and its ramifications. Both states started small and had several factors in common in their growth, for instance the quest for furs, not mentioned by Stent and underemphasized by Grandin. McCullough describes Ohio as a land of great resources, but his main interest is in the high purpose of white expansion into the territory. In short, the proffered motives and results of expansion in these three books lead in profoundly different directions.

Grandin’s chief villain is Andrew Jackson (Donald Trump’s favorite president), who massacred Creek Indians in 1814, oversaw Indian removals from the East in 1830, and owned slaves. For Jackson and many others, the West–wherever it happened to be–provided relief for the whole country. Expanding westward focused people’s attention on the frontier and provided distraction from social and economic problems back east. Americans could at least dream about going west to start a new life. The West was always touted as a site of freedom. But along the way, U.S. troops committed many crimes, among them rape, murder, and destruction of churches in the Mexican War of the 1840s. Such acts occurred again in the following decades, especially in our war in the Philippines, 1899-1902, but also in Nicaragua in the 1920s and in other countries.

Although many of these stories are well known, Grandin weaves them together in moving and depressing fashion. He also ties the wars on the frontier and abroad to wars at home, above all the Civil War but also “race war” and violent repression of socialists and labor unions. Together, these fights, which used up money and energy, help explain the absence here of “the social-democritization of European politics . . . including the rights to welfare, education, health care, and pensions” (95). Attention to people’s needs at home lost out to the settlement, but even more to the idea, of the frontier. By the 1840s, the U.S. was “becoming inured to its [own] brutality and accustomed to a unique prerogative: its ability to organize politics around the promise of constant, endless expansion” (94).

Grandin portrays white movement west as a pattern of broken treaties and ethnic murder or cleansing. Andrew Jackson is little more than a crude butcher. Close behind in villainy is Thomas Jefferson, who also gushed about “the West” but never traveled farther toward it than the Shenandoah Valley. Jefferson justified American westward expansion as the spread of goodness and light. However, he wrote in 1813 that “all our labors for the salvation of these unfortunate [Indian] people have failed” because of England’s support for them. It would be “preferable” to “cultivate their love,” he said of the indigenous folk, but “fear” would also work. “We have only to shut our hand to crush them” (43). Thus rapacious frontiersmen strode forth to make a beautiful new world for themselves in the wilderness, relying all the way on mass violence. Grandin’s view of American expansion is relentlessly grim.

Happier are the believers in McCullough’s “heroes” in the settlement of Ohio. The dust jacket calls them “dauntless pioneers who overcame incredible hardships to build a community based on ideals that would come to define our country.” McCullough lauds the selfless careers of Manesseh Cutler, a minister and master of all sciences, and his son Ephraim. They played key roles in leading white settlers into Ohio in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and in the state’s early law-making. They believed in and practiced democracy and insisted successfully that slavery would not be introduced beyond the Ohio River.

Manasseh Cutler helped draft key provisions of the Northwest Ordinance (1787). Filled with stirring words, it insisted on freedom of religion and “morality and knowledge” spread by “schools and the means of education,” with all overseen by “good government.” The Cutlers and friends also promoted the “New England system,” in which “the establishment of settlements [would be] done by legal process, and lands of the natives to remain theirs until purchased from them” (7). Suppose they didn’t want to sell? That possibility was not explored in the Northwest Ordinance. Indian rights proved not to be a problem because beyond the Ohio River lay “howling wilderness” (7; McCullough is quoting a contemporary source).

The Treaty of Greenville (1795) opened the way “to clear and cultivate lands that had never known the axe and the plow” (118, quoting George W. Knepper). Here is the old “empty land” (terra nullius) idea, although Indians had cultivated the earth in various parts of Ohio. “Empty” meant that civilized people had the right to take it. In McCullough’s narrative, Indians were obstacles to the spread of American greatness. He rhapsodizes that, “West was opportunity. West was the future.” Achievements in Ohio, McCullough writes, “would one day be known as the American way of life” (13).

McCullough abandons the pretense of a dispassionate history in his subtitle. His book is a paean to American goodness; it ends with the idea that the Cutlers et al. overcame the “adversities they faced, propelled as they were by high, worthy purpose. They accomplished what they had set out to do not for money” or fortune or fame, but to “advance the quality and opportunities of life–to propel as best they could the American ideals” (258).

Angela Stent tries to achieve some detachment in outlining Russia’s past concern with borders and the country’s goals and fears at present. She occasionally grants that Russians might have a point of view worth mentioning about the near abroad. She notes that George W. Bush’s “Freedom Agenda” advocated regime change in Georgia and Ukraine. Mistakes and insults to Russia from the American side are introduced; for example, U.S. officials misled Yeltsin about the EU’s extension to Eastern European countries. Russian Prime Minister Yevgeny Primakov learned about NATO’s bombing campaign against Serbia in 1999 only when he was in mid-air en route to Washington to discuss a solution to genocide in the former Yugoslavia.

NATO “made a major mistake” in 2008 when it “mishandled” enlargement to ultimately take in Poland and the Baltic States (129). But for Stent, the major problem is that “NATO” did not think through the implications of a military pact with those countries. Are the Baltic states “defensible,” she asks (127)? (A far better question would be what would Russia gain by conquering those countries, even if no shots were fired? More sand and gravel?) Supposedly “the Russians” are deeply chagrined by the loss of their empire, and they want it back. Looking at events in Georgia in 2008 and in Ukraine 2013-14, Stent asks, “What is it that propels this Russian drive for expansion?” (17).

The “drive” is connected to the Russian people. Stent mentions that many foreigners who went to Russia for the World Cup matches in 2018 brought with them “stereotypes about unfriendly Russians living in a backward country.” However, at least some visitors discovered “normal” people there, ones who could smile and party. Then we learn that they can no longer celebrate in the streets (2).

Stent announces that, “To understand Putin’s world, one has to start with the history and geography—and, yes, culture, that shaped it.” American and British readers apparently must be told that Russia possesses a culture and exhorted to think of the country’s people as “normal.”

Of course Stent discerns an “iron hand” ruling the country under both tsars and Soviets (22), although in 2005 “the government was forced to back down” after protests by pensioners about “reforms” in their payments (41). Whatever the “hand” might be, Stent insists that the U.S. can engage Russia where that country has a national interest.

Along among the three books, McCullough suggests that expansion was based on high ideals. But Americans apparently have the right to bring civilization not only to those Indians or Filipinos we have failed to kill, but also to the Vietnamese, Iraqis, Afghans, and so on. If National Security Adviser John Bolton seems like a rabid dog in his eagerness for more war, it is well to remember that he is part of a long tradition that sees American greatness as a justification for imposing our will (there should be no talk of ideals) on other peoples.

Grandin’s book, more solidly argued, will sadden some people–though surely far fewer will read it than will pick up McCullough’s. However, Grandin conjures up a social democratic paradise in Europe that does not exist. Or, if it does, it is limited to a few northern European countries that today evince a certain distrust of democracy and ugly ethnic prejudices. In his eagerness to criticize domestic life in the U.S., Grandin sometimes goes too far. He mentions lynching repeatedly, for example as part of the “relentless race terror African Americans faced since the end of Reconstruction” (130). Yet much recent work on lynching shows that it was erratic and fell, with some short upward movements, steadily after 1892. See studies, for example by Michael Pfeifer, Fitzhugh Brundage, Stuart Tolnay and E. M. Beck, and myself. Lynching was always horrible, but in my view it cannot be described as “relentless” or as a system. Moreover, Grandin is not interested in the rise of land ownership or a middle class among African Americans, despite the great odds against them. (Yes, they lost great amounts of that land later.) Nevertheless, his dark vision explains much about American policy at home and abroad.

In Stent’s Russia, expansion and the “iron hand” go together. But what does that phrase mean? Did people not live and love, at least a little, on their own terms? I’ve been to a lot of Russian parties, starting in 1978, where talk and vodka flowed together, and I would say yes. The concept of “lived socialism” (e.g. Mary Fulbrook, Wendy Goldman) should be considered by the Washington circle. And, if there has been an “iron hand,” how can anyone explain the Soviet victory in World War II (no, the NKVD did not drive troops into battle; see Richard Reese), mass mourning at Stalin’s death, his popularity in many recent polls, and Putin’s own popularity?

Russians are always subjects, never actors in accounts like Stent’s. Denigrating Russians is an old tactic. Stent cites George Kennan in Russia and the West under Lenin and Stalin (1961), where he mentioned the then-accepted estimate of twenty million Soviet dead in World War II. He added, “But what are people, in the philosophy of those who do not recognize the existence of the soul?” (Russia and the West, 275). Kennan liked the work of the Marquis de Custine published in 1841, also cited by Stent—but without a key passage. Custine wrote that “real barbarism” characterized Russia; the inhabitants were “only bodies without souls.” In an “empire of fear,” foreigners are “astonished by the love of these people for slavery.” The trail then leads back to another travel account that Kennan, and surely Stent, knew, Sigismund zu Herberstein’s best seller on Muscovy. His book was first published in Latin in 1549, then translated into multiple European languages. Herberstein found that, “It is debatable whether such a people must have such oppressive rulers or whether the oppressive rulers have made the people so stupid.”

During the Cold War, high American officials loved Custine. Zbigniew Brzezinski, for instance, wrote in 1981 that, “No Sovietologist has yet improved on de Custine's insights into the Russian character and the Byzantine nature of the Russian political system.” None of Custine’s leading American devotées disavowed his or Herberstein's final judgments on Russians.

There is one nearly useless map in Stent’s book, a cluttered view of Eurasia crammed onto a single page. She does not provide a map showing the expansion of NATO over time up to Russia’s borders. Would that expansion not have made normal people in Russia quite nervous?

Stent writes that, “There is no precedent in Russian history for accepting the loss of territory, only for the expansion of it” (17). Then at the bottom of the same page, she insists that since the fifteenth century, Russia “has constantly alternated between territorial expansion and retreat.” She might have considered that from the 1760s on, Russia/USSR has “retreated” from France, Manchuria, Austria, Hungary (twice), part of Finland, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, northern Iran, the Baltic states, and Germany (twice or more, depending how you count matters).

Yet even a cursory look at Russian expansion shows that much of it was defensive: the Tatars (Mongols) attacked deep into Russian settlements in the south and east every summer in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. These raids were not the response of scattered tribes who often despised each other; they were military expeditions organized by the heirs of the original Mongol Horde that had conquered Russia in the thirteenth century. In response to the continuing attacks, which reached Moscow as late as 1571, the Muscovite government extended a string of forts (the zaseka) further and further south. The culmination of this drive was the conquest of Crimea in 1783 by a Russian imperial army from a Tatar remnant.

Catherine II then reportedly said, “That which stops growing begins to rot. I have to expand my borders in order to keep my country secure” (17, no source given). Shades of Grandin! But to suggest that internal security was the motivation for Russian expansion is to miss essential parts of the country’s history.

In the nineteenth century, Russian expansion was typical of the lust for more territory among all major European powers, the U.S., and the Japanese. In 1944-45, the Red Army marched into Eastern Europe to push the Germans out, with full Western approval.

Nothing in America’s past resembles the recurring invasions of Russia by foreign powers, from the Mongols in the thirteenth century to the Germans in 1941. Sometimes, as in the early seventeenth century, assaults came simultaneously from several directions. If Russians are sketchy on the details of these campaigns or exalt their own victories, they still base their outlook today on the knowledge that these incursions happened. Stent is not much interested in this past.

More than five years out from the Ukrainian crisis of spring 2014, little indicates that Russia covets more territory anywhere. Annexation of the Crimea involved a region that was never Ukrainian in any profound sense. The war with Georgia in 2008 also resulted in Russia’s absorbing new land, but areas not populated by Georgians. Seeing some “drive” for endless conquests in these affairs, however much they broke international law, is gross speculation and is not based on a serious examination of Russian history.

Stent has a lot of valuable detail and some useful insights into Russian concerns. But what rational interests would a nation of dead souls have? Her book becomes at once more suspect and more valuable when read together with Grandin’s examination of American frontiers. In turn, Grandin will infuriate or dishearten fans of David McCullough’s glorious American past, which in its argument could serve as a foil to Russia’s supposedly limitless, ugly ambitions. Could we at some point adduce Britain in the nineteenth century or Germany in the twentieth? Could we just watch Game of Thrones?