An Interview with "Most Wanted" Author Sarah Jane Marsh

Chelsea Connolly: While reading Most Wanted, it occurred to me that I couldn’t remember the last time I had read a children’s book, and your book helped remind me of how unique of a medium they are. Could you talk about what you enjoy most about being a children’s author?

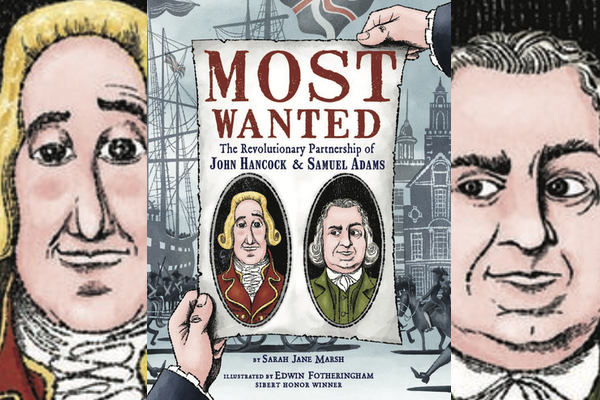

Sarah Jane Marsh: I love the design challenge of crafting compelling nonfiction for children. I start with a vision of a story I’m fired up to share with kids. In Most Wanted, I wanted readers to understand why John Hancock and Samuel Adams were called out by name as troublemakers by the British government (reminiscent of our current U.S. President name-calling on Twitter). In the process, I’m whisking readers through ten years of American Revolution history...all in less than 2500 words.

It’s challenging to channel all this inspiration and research into a compelling story within the format of a picture book biography. I’m writing to engage my young reader, but I must also consider the needs of the illustrator, publisher, teacher, and librarian. And the magic of narrative nonfiction is that it reads like fiction yet is historically accurate. So one immediate challenge is employing fiction techniques, such as narrative arc, character, pacing, and dialogue, without straying from the facts. And word count is my toughest constraint. An ideal nonfiction picture book is less than 2000 words. Each word has to hold its weight.

Children's books are just as much a visual medium as they are textual. This puts a great deal of responsibility on the illustrator as well as the author. What is the relationship between an author and an illustrator when crafting a children's book? How do you help and/or influence each other?

Interestingly, the author and illustrator don’t usually have direct contact. Our work passes through our editor and art director who help orchestrate the story. But it is important for the illustrator to first create their vision based upon the completed manuscript. This begins with sketches that my editor sends to me for comment. It’s my job to weigh in if something doesn’t work historically. I do compile resources for our illustrator from my research: images and primary source descriptions of buildings, objects, clothing, etc. My publisher also employs a historian to fact check both the manuscript and illustrations.

I also share my thoughts about overall theme and context. In both Most Wanted and Thomas Paine and the Dangerous Word, it was important for me to have a visual sense of “the people.” Although I use individuals such as Adams, Hancock, and Paine as a vehicle for the story, I want readers to understand the American Revolution was ultimately a mass movement of the people. My editor shared this insight with our illustrator of both books, Edwin Fotheringham, who crafted some amazing scenes such as the 5,000 Bostonians who gathered at Old South Meeting House on the evening before the protest now known as the Boston Tea Party. We also had fun with the final illustration by adding some famous folks of the American Revolution.

Visual literacy is also an important skill for young readers. With picture books, the illustrations enhance the story in many ways, such as by adding context, explaining vocabulary, or expressing emotion. Ed brilliantly depicted the oppressive nature of the Stamp Act through a visual metaphor of a super-sized stamp falling from the sky as John Hancock obliviously sips his beloved Madeira wine. Ed added an incredible amount of historical detail in Most Wanted, especially impressive considering he’s from Australia!

The causes of the American Revolution is a very dense subject. How did you choose to tell this specific story?

My picture book biography on Thomas Paine focused on the personal story behind the famous pamphlet Common Sense. As a result, readers gain an understanding of how and why we declared independence. (Insider secret: underneath the jacket cover is a replica cover of Common Sense!)

For Most Wanted, I was curious about General Thomas Gage’s 1775 proclamation pardoning all militia gathered outside Boston -- except for Samuel Adams and John Hancock. What trouble had these two men caused to be called out by name? In the process of writing this story, I realized I was creating a prequel, history-wise, to Thomas Paine.

At first, I approached this story by focusing on the legendary hectic night inside the Hancock-Clarke house before the battles in Lexington and Concord. I spent a year writing this story. And my literary agent wasn’t wild about the resulting manuscript. But she was intrigued by the relationship between Hancock and Adams. So using that as my new lens, I expanded the story across ten years of revered (pun-intended) history, taking readers from the Stamp Act through the protests in Boston, the fighting in Lexington and Concord, to Hancock and Adam’s triumphant entrance into Philadelphia for the second Continental Congress, and ending with General Gage’s proclamation. This gave me the opportunity to compare and contrast these two leaders, and show the cause and effect of events that led up to the fighting Lexington and Concord.

When the final book arrived on my doorstep, I was thrilled to discover that our editorial team had surprised me by recreating Gage’s proclamation underneath the jacket cover -- similar to our Paine book. A total delight!

The author's note at the end of your book addresses that traditional narratives of the American Revolution often ignore and silence the populations who suffered greatly at the hands of the colonists. How did you incorporate this complexity in the book itself? How do you strike a balance between addressing nuance while also keeping the story accessible to children?

My author’s note, written closer to publication, reflects an awareness I didn’t have when I began writing Most Wanted in 2015. My focus was navigating the complexities of the confusion prior to the fighting in Lexington and Concord. As engaging as the story is, my ten-year history sticks to the traditional narrative that we are beginning to see as limited and one that omits the experiences of those who did not hold power at the time, such as women, African Americans, and Native Americans. In Thomas Paine we address the issue of slavery directly, as Thomas Paine did in his writings. In Most Wanted, the topic is alluded to in the illustrations, but not addressed in the text other than a hypocritical quote by Hancock declaring he “will not be a slave” in the presence of his enslaved servant.

By listening to the deeply knowledgeable voices challenging our traditional narratives, I began to see how we have distorted our understanding of our history and of ourselves. My author’s note is my attempt to correct course, prompt discussion of the limitations of the text, and encourage critical thinking about these narratives, our history, and of ourselves.

There is an awakening happening in American history. Books like Hidden Figures, Never Caught, Stamped From the Beginning, and the New York Times “1619 Project” are examples of how a new age of historians are delving into our past to share silenced voices, experiences, and accomplishments. Howard Zinn was an early voice in this realm. And traditionally, our history has been told primarily by white males through their perspective. That is changing. And we are seeing the effects and gaining a better understanding of our shared history.

Children’s publishing is also experiencing an awakening, thanks to the efforts of those pushing to address the inequality of representation in children’s books. Only 23% of children’s books depict characters of diverse backgrounds. And there is good discussion and groundbreaking books that address tough topics with kids. In nonfiction, nuance can be discussed more fully in the backmatter. Every child, especially those dealing with tough situations, deserves to be seen in a book. In many ways, we explain the world to ourselves and our children through our books. Storytelling is our most powerful medium for transmitting values.

Much of the work you do as an author can be translated to the work a teacher does in the classroom. As a former elementary and middle school teacher and having taught in the classroom yourself, what advice would you give to educators who want to talk about these complex and often upsetting issues with their young students?

I think it’s important for educators to first develop their own cultural competency. Like learning itself, it’s a lifelong journey and one that I’ve recently begun through books, discussion, online resources, and trainings available to guide this growth.

Cultural competency starts with a better understanding of self: an awareness of our own identity and how we’ve been socialized within our own culture to hold certain norms. For example, it was eye-opening to realize that the books I read as a child universally featured white main characters. This inherently reinforces a bias that the white experience is the norm. When you become aware of your biases, you can work against them -- for example, by reading and sharing authors outside your race, gender, culture, sexual identity, etc. As Stephen Pinker wrote, “reading is a technology for perspective-taking.” It’s important to recognize these biases in our classroom and curriculum, understand how they negatively affect our students, and actively seek and share broader viewpoints. Doing this with your students can help develop their cultural competency as well. And culturally responsive teaching builds on that competency by seeking to understand the diverse cultures and identities of our students and incorporating them into our classroom. All students should see themselves represented and reflected in their learning at school.

Most importantly, use available tools. Teaching Tolerance is a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center and has a wealth of resources for teaching hard history and how to sit with that discomfort. Welcoming Schools has tools to create LGBTQ and gender inclusive schools and to prevent bias-based bullying. Books like An Indigenous People’s History of the United States and Stamped provide an eye-opening understanding of our history and have a version for teens, a powerful tool for the classroom.

These resources also provide important frameworks. For example, how and why we teach about complex and upsetting issues are important. Students need to know about the violence and oppression in our U.S. history of enslaving other humans, but also the many acts of resistance by enslaved people and the beautiful cultures that survived this brutality. (Kwame Alexander’s picture book The Undefeated does this well with African American history and won the Caldecott Medal, a Newbery Honor, and the Coretta Scott King Award.) Similarly, Mexican and Native Americans experienced many of the same injustices and violence as African Americans, but this is rarely taught in the classroom. Celebrating these resilient, thriving cultures is an important part of the education we need to impart.

What do you hope that children take away after reading Most Wanted?

I hope that Most Wanted inspires readers to want to read and learn more about our nation’s history. The American Revolution is not always taught in elementary school, and I hope this book sparks a curiosity to learn more. My own fascination with the American Revolution was inspired by reading Laurie Halse Anderson’s picture book Independent Dames about the courageous women of that era. One book can be a doorway to further exploration.

Also, I hope that my author’s note prompts my young readers and the adults in their lives to engage in critical discussion about the book, this era, and our history as a nation. And to seek out expanded viewpoints and fill the gaps in their own knowledge with more learning. Our history is fascinatingly complex and surrounds us still today.

Do you have any ideas in the works for future projects?

I am re-evaluating my role as a historian and storyteller for children. I want to use the agency I have in the publishing world to broaden our children’s understanding of our nation’s history and to think critically, engage in democratic discourse and ultimately, to paraphrase Martin Luther King Jr., help bend the long moral arc of the universe toward justice.

I’m working on another picture book that tackles the issues that I’ve been wrestling with as an author. It looks at America through a social justice lens to prompt conversation. I can’t tell if it’s brilliant or terrible, but I’m enjoying the creative challenge!