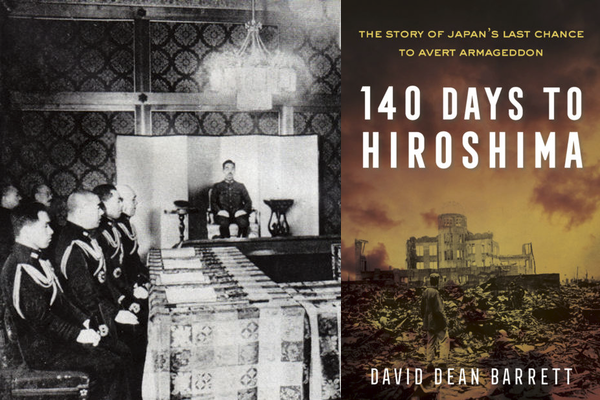

The Atomic Bomb, War Room Intrigue and Emperor Hirohito's Decision to Surrender

As the world observes the 75th anniversaries of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki later this year, Americans have still not reached a consensus about the role of the atomic bomb in Japan’s surrender. Was Japan ready to surrender without the bomb? Some of us believe so, in particular if the Allies would have simply guaranteed the preservation of the Imperial System (with the divine Emperor as the embodiment of all sovereign power in the realm). Others contend the Soviet entry into the war actually caused Japan’s surrender.

However, a close look at the deliberations of Japan’s Supreme Council at the Direction of War––known as the “Big Six”—evidence which has been available for decades, shows Japan’s leadership deeply divided into two factions. A hardline contingent remained opposed to surrender even after the second atomic attack on Nagasaki and the Soviet Union’s entry into the war. On the flip side, the peace faction used the atomic bombings to engage the Emperor in the surrender decision, an unprecedented move within Japan’s dysfunctional form of government, which required unanimous approval to make any decision.

By the summer of 1945, the United States and Japan had finalized their plans for the battle for mainland Japan. Paramount in President Harry S. Truman’s mind were the expected American losses. Multiple sources in the American military estimated the invasion of Japan would result in a quarter of a million to one million U.S. soldiers killed and four times those numbers in total casualties. They also predicted five to ten million Japanese deaths in the invasion; the Japanese themselves thought the total could reach twenty million.

From May until early August, Japanese Foreign Minister Shigenori Tōgō, at the behest of the Big Six, carried on a series of vague communications with the Russians that proved futile and never broached the subject of unconditional surrender, an Ally demand since January of 1943. On July 18, Japan’s ambassador to the Soviet Union, Naotake Satō, sent Tōgō a message saying that the Japanese must accept the equivalent of unconditional surrender, excepting the preservation of the Imperial System. Tōgō flatly replied, “With regard to unconditional surrender, we are unable to consent to it under any circumstances whatever.”

On July 26, the Allies––excluding Russia––gave Japan an ultimatum known as the Potsdam Declaration. Thirteen terms were listed in the declaration, a break from the blanket unconditional surrender imposed on Germany. For Japan, unconditional surrender had only been applied to Japan’s military. The Allies also included two warnings, that Japan must surrender now or face “prompt and utter destruction” and that the Allies would “brook no delay.” Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki rejected the declaration, calling it “a thing of no great value.”

On August 6, the U.S. exploded the first atomic bomb used in combat over the city of Hiroshima. The Big Six did not meet until three days later on August 9, the same day that the Soviets entered the war against Japan and the United States detonated a second atomic bomb over Nagasaki. The previous day, the Emperor had told Tōgō: “Now that this sort of weapon has been used, it is becoming increasingly impossible to continue the war. I do not think it is a good idea to miss an opportunity to end the war by attempting to secure advantageous conditions.”

Nevertheless, the members of the Big Six remained at odds throughout the 9th. The peace faction, which included Suzuki, Tōgō, and Navy Minister Admiral Mitsumasa Yonai, wanted to surrender, preserving only the Imperial System. But War Minister General Korechika Anami, Army Chief-of-Staff General Yoshijirō Umezu, and Navy Chief-of-Staff Admiral Soemu Toyoda demanded three additional conditions: limited occupation or none at all, control of war crimes trials, and control of the disarmament of the nation’s military. Absent these, they wanted to fight the decisive battle on the Japanese homeland, believing they would inflict such high casualties that they could achieve better terms.

After hours of heated debate, the peace faction managed to out-maneuver the hardline militarists and convene an Imperial Conference to get the Emperor’s opinion on an issue that clearly had not been agreed upon unanimously. After hearing both sides of the argument, Hirohito told his government he favored the peace faction’s proposal.

Baron Kiichirō Hiranuma, President of the Privy Council, demanded that acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration be contingent on "the understanding that the said declaration does not compromise any demand which prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty as a Sovereign Ruler.” This proviso preserved the Imperial System and retained Hirohito as Emperor and head of the Japanese government. Anami extracted one further requirement, a promise from the cabinet that the war would continue should the Allies reject the Japanese offer.

Upon learning of the offer, Truman immediately called a meeting with Secretary of War Henry Stimson, Secretary of State James Byrnes, Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, and his Chief of Staff Admiral William Leahy. “Could we even consider a message with so large a ‘but’ as the kind of unconditional surrender we had fought for?” he asked. Forrestal, Stimson, and Leahy wanted to accept the Japanese offer. Stimson said allowing the Japanese to keep the Emperor served American interests by encouraging the military to lay down their arms. Byrnes demurred. In his view, Japan’s phrasing amounted to a refusal to accept the Allies’ offer. Forrestal suggested that some changes to the wording might make the offer acceptable—an idea that appealed to Truman, who asked Byrnes to come up with a counteroffer acceptable to the Allies.

Byrnes’ response contained two key points: first, that “the authority of the Emperor… shall be subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers,” and second, that “the ultimate form of government of Japan shall, in accordance with the Potsdam Declaration, be established by the freely expressed will of the Japanese people.” Upon receipt, the Japanese government relapsed into stalemate for two and a half days, with Anami, Umezu, Toyoda, and Hiranuma demanding acceptance of their original four conditions or continuation of the war.

On the morning of August 14, American B-29 bombers released millions of leaflets over Japan describing the surrender negotiations. Marquis Kōichi Kido, the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal and the Emperor’s most trusted advisor,found one and warned the Emperor that the leaflets might provoke a rebellion, since the peace negotiations had been kept secret from the Japanese people and military. The Emperor instructed Suzuki to muster another Imperial Conference, where, if necessary, he would “command” the cabinet to accept Byrnes’ counteroffer. After listening to Anami, Umezu, and Toyoda’s now familiar arguments for rejecting the Allies terms, Hirohito told his government he wanted the Byrnes offer accepted.

The record of the Imperial Conferences extinguishes any notion that the Japanese government was ready to surrender, that it would have surrendered had the Allies guaranteed the Imperial System, or that it surrendered in response to Russia’s entry into the war. It makes clear two salient facts: that Emperor Hirohito ended the war, and he ended it because of the atomic bomb. He stated as much on four separate occasions: at his meeting with Tōgō on August 8, in his Imperial Rescript (considered by the Japanese to be an inviolable statement from their divine Emperor) on August 15, in a letter to his son on September 6, and when he told Supreme Allied Commander General Douglas MacArthur on September 7 that “the peace party did not prevail until the bombing of Hiroshima created a situation which could be dramatized.”