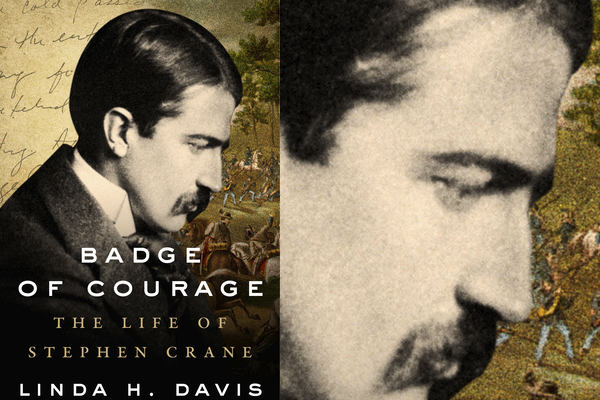

Why the Short and Rebellious Life of Stephen Crane Still Matters

He was the personification of cool: young, talented, rebellious. Author of the classic novel The Red Badge of Courage. A war reporter. A man who stood up to the New York Police to defend a prostitute falsely accused of soliciting. A survivor of a shipwreck he wrote about in one of his best short stories, “The Open Boat.” World famous at twenty-four, dead at twenty-eight. “My name is Crane, Stephen Crane,” he said, evoking James Bond.

Not many writers have lives made for the movies; Stephen Crane did. He burst out of the starting gate at a gallop, kicking up his share of admiration and resentment. His plot-driven life is full of memorable scenes. There he is, being chased on horseback by Mexican bandits during a reporting trip to the American Southwest; sleeping on a pile of saddles in Cuba during the Spanish-American War; leaving America for England with one woman while professing his love to another; presiding over an ancient English manor equipped with a ghost.

With his “melancholy beauty,” and his remarkable gray-blue eyes, “full of luster and changing lights,” said Willa Cather, he even looked like an actor.

Add his personality to the picture. Stephen Crane’s gift for storytelling was not confined to his written work. Those who heard Crane tell the true story of the shipwreck that inspired “The Open Boat” found it even more enthralling than the written version.

An English professor of mine used to say that literature teaches us how to be human. If biography offers the further advantage of being true (to the extent that we can ever know another person’s truth), the meteoric life of Stephen Crane exemplifies the human struggle, what William Faulkner called “the human heart in conflict with itself.”

Crane’s life was one great battle to get at the truth, at any cost. During a February blizzard in New York, with winds up to forty miles an hour, his skin burning from the cold, he stood for hours in a breadline, wearing only a thin layer of clothing – then managed to get the experience down on paper, though he was suffering from exposure. Asked why he didn’t put on more clothes, he said, “How would I know how those poor devils felt if I was warm myself?” Reporting on the Spanish-American War, he got right into the trenches with the signalmen, who were being fired on, then surveyed the action on horseback – until he was ordered to get down.

And there is this snapshot: Forced to leave Cuba after President McKinley signed a peace protocol proclaiming an armistice, Crane was observed weeping as he parted with his horse – a “hammer-headed, spur-scarred” kicker and biter with whom Crane, a superb rider, “got along like sweethearts,” said a fellow correspondent.

He soon got into trouble. Having already infuriated the New York Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt by calling out a bad cop for falsely arresting a prostitute, Crane outed the Rough Riders for stumbling into an ambush on first arriving in Cuba in the Spanish-American War, thus sealing Roosevelt’s enmity. At the beginning of what promised to be a brilliant career, Crane couldn’t go to New York without risking arrest.

Decide for yourself whether Stephen Crane took foolish or admirable risks. Physically frail all his life, he had reason to believe that he wouldn’t live long, that he didn’t have time to waste. Utterly dedicated to his craft, he was hellbent on getting at the real thing, consequences be damned.

A.J. Liebling described The Red Badge of Courage as a timeless tale “about a boy in a dragon’s wood.” He might have said the same thing about the author. Young all his brief life, Stephen Crane faced his fears and turned them into poetry. Though he also wrote a lot of hackwork to stay ahead of his creditors, and, by his own admission, “managed his success like a fool,” he never quit. Almost until his last breath, and after long suffering, he was dictating a novel.

Stephen Crane matters because of The Red Badge and a handful of short works which teach us how to be human. But for all the brilliance and originality of Crane’s best writing, which is not something you can pick up by osmosis, it is perhaps the man himself and his dedication to truth that we can hope to learn from. A trailblazer, he never let adversity get in his way. He would not be held back by circumstances, intimidation, opinions. And in this steadfastness, his life story – messy, glorious, improbable, heartbreaking – seems to me very much one with the American Spirit. At a time when America is backsliding, truth is under daily assault, and the country is more divided than it has been since the Civil War, Stephen Crane, a nineteenth-century man who paid a heavy price for his truth-telling, and was a rebel in his time, is a rebel for our time, too.