Telling Chestnut Stories

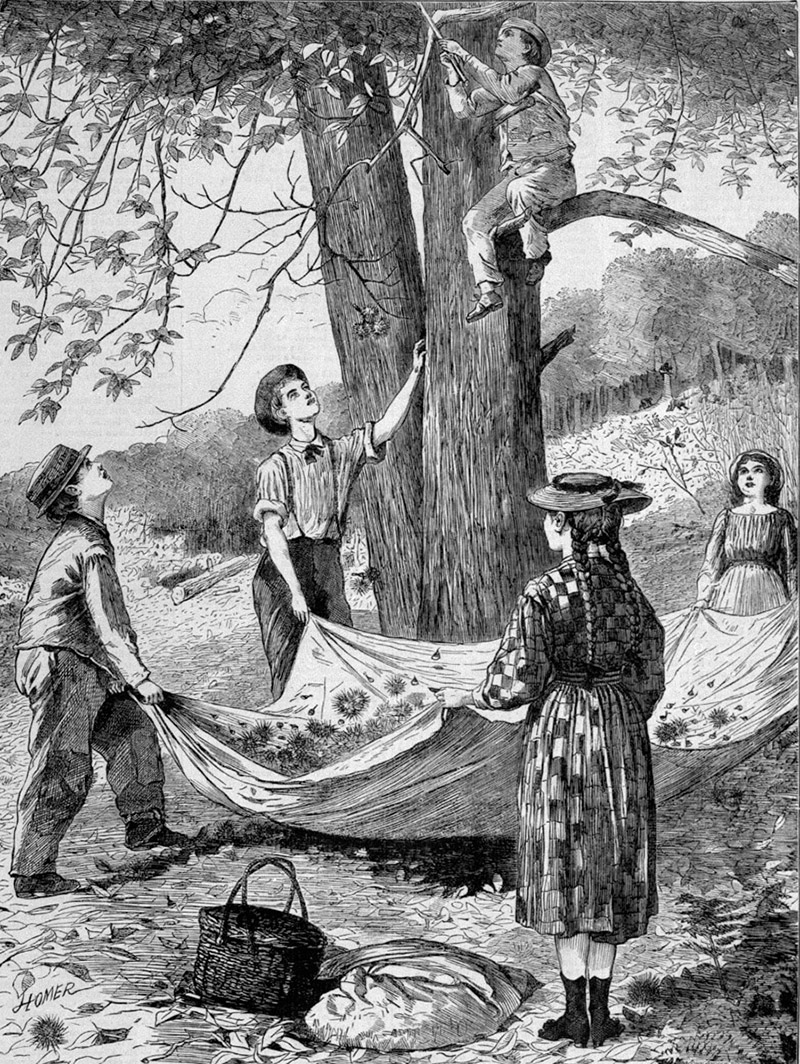

Chestnut Trees in Bloom, by William Henry Holmes. [Smithsonian American Art Museum]

At one time, more than 4 billion American chestnut trees spread from southern Canada all the way to Mississippi and Alabama. While it was rarely the dominant tree in the forests, this giant of the eastern woodlands was hard to miss. It could stand over one hundred feet tall, the trunks straight and true.

To those who lived in the eastern United States, especially Appalachia, the tree was invaluable. It provided food for both people and animals and wood for cabins and fence posts. In cash-poor regions, the tree could even put some money in people’s pockets when they sold nuts to brokers to take to the cities of the Northeast. Some joked that the tree could take you from the cradle to the grave, as the wood was used to make both furniture for babies and caskets. It was certainly “the most useful tree.” In the early 20th century, however, the chestnut came under serious threat. A fungus, first identified in New York in 1904, began killing chestnut trees. It quickly spread south across Appalachia, resulting in the almost complete loss of the species by the mid-20th century. This loss had enormous ecological impacts on the forests of the eastern United States and contributed to a decline in the population of many species of wildlife, including turkeys, bears, and squirrels.

Today, while millions of American chestnut sprouts remain in the forests of the East, almost all the large trees, as well as most of the people who remember the trees’ dominant place in the forest ecosystem, are gone.

Since 1983, the American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) has taken the lead in restoring the American chestnut. While scientists coordinate the project, volunteers play an important part in planting and caring for trees in TACF test orchards. One of the tools TACF uses to connect with volunteers are chestnut stories. In TACF’s publication, originally published as the Journal of the American Chestnut Foundation and known since 2015 as Chestnut: The New Journal of the American Chestnut Foundation, chestnut stories can take many forms — oral histories, essays, poems — but they all document the relationship between humankind and the American chestnut tree. Chestnut stories serve an important purpose: reminding people of the value of the species and the many ways people used the tree before its decline. In documenting the story of the American chestnut through the journal, in sharing and interpreting this story, and in using it to mobilize volunteers and resources, TACF has demonstrated the value that practices rooted in the field of public history and the study of memory can bring to the realm of environmental science. Public historians are well aware of the power that narrative has in prompting action and encouraging people to rethink the status quo. The chestnut stories documented by TACF help create a historical narrative and also serve as a justification for the reintroduction of the species into the modern landscape. As we deal with the long-term consequences of climate change, the emergence of new diseases, and the loss of habitat, the work of TACF can, perhaps, provide a road map for other organizations to employ science, technology, public history practices, and memories to mobilize people to solve environmental challenges.

While it is difficult to pinpoint the exact moment when the fungus that devastated the American chestnut arrived in North America, it is possible to date when and where someone first noticed its effects. In 1904, in the Bronx Zoological Park in New York City, employee H.W. Merkel noticed that large sections of the park’s chestnut trees’ bark were dying, and the overall health of the trees appeared to be deteriorating. Dr. A.A. Murrill, who worked for the New York Botanical Gardens, was called in to study the affected trees. He identified the cause: a new fungus, which he called Diaporthe parasitica (the name was changed in 1978 to Cryphonectria parasitica). It is highly unlikely that the trees in the Bronx Zoo were the first to be infected by the fungus, which had come into the port of New York from Asia, but rather it was the first place that someone paid enough attention to notice it.

The “chestnut blight,” as it was commonly called, spread quickly, infecting trees in other locations in New York, as well as in New Jersey and Connecticut. Scientists studying the blight, such as Dr. Haven Metcalf and Dr. J.F. Collins, published bulletins about the disease, which contained recommendations for how to slow the spread. These recommendations included checking nurseries for blighted trees and quarantining those suffering from the blight, creating blight-free zones where chestnuts were removed in the hopes that the blight’s progress would be stopped if there were no chestnut trees, and performing surgery to remove cankers from infected trees. Unfortunately, the advice they gave did not stop the blight, and it began pushing farther south. In Pennsylvania, the Chestnut Blight Commission had permission to enter private property and remove trees infected with or threatened by the blight. In all, the commission spent over $500,000 to fight the blight. But, again, their efforts did not halt the spread. The blight reached West Virginia by 1911, pushing into the heart of Appalachia, where the tree had an important place in the lives of mountain communities. Combined with ink disease, which had been attacking chestnut trees in the southern end of the tree’s range since the 19th century, the blight caused widespread devastation. By 1950, 80% of the American chestnut trees were gone. In all, the upper portion of over 3.5 billion trees died, the equivalent of approximately 9 million acres of forest. The root structure of many trees, however, did not die, and stump sprouts continue to emerge from root systems today, well over a century later. Unfortunately, before they are able to grow very large, these stump sprouts become infected by the blight and die back. So today, while millions of stump sprouts do exist, few mature trees are left.

TACF eventually took the lead in chestnut restoration efforts. TACF began formally documenting its progress in 1985 with the publication of the Journal of the American Chestnut Foundation, published as Chestnut: The New Journal of the American Chestnut Foundation since 2015. In the first edition, the then editor Donald Willeke lays out the mission of the journal: “We hope that it will be both a scientific journal and a means of communicating news and developments about the American Chestnut to dedicated non-scientists (such as the lawyer who is writing this Introduction) who care about trees in general, and the American Chestnut in particular. and wish to see it resume its place as the crowning glory of the American deciduous woodlands.” Over the years, the journal has moved from a volunteer publication released once or twice a year (depending on the year and on capacity) to a glossy, professional magazine released three times a year.

In the journal, the progress of the backcross breeding program is broken down into terms nonscientists can understand. The journal, however, is not only about the science behind the restoration effort. One of the most significant sections of the journal in its early years was the “Memories” section, which documented “chestnut stories.” While many of the memories included in the journal came to TACF unsolicited, TACF also recognized the importance of documenting people’s chestnut stories in a more organized fashion. In 2003, the then membership director Elizabeth Daniels wrote about the American Chestnut Oral History project, which aimed to preserve chestnut stories for future generations. In the spring of 2006, the then editor Jeanne Coleman let readers know she was interested in gathering chestnut stories. Stories came pouring in, and as Coleman says in the fall 2006 issue, “These stories are heartwarming [and] often funny.” Today, in essence, the journal itself acts as the archive of TACF’s chestnut stories, preserving and sharing them simultaneously.

In reviewing all 79 issues of TACF’s journal that are available online as of January 2022, as well as other sources, the significance of the chestnut stories becomes quite clear. The work of the scientists engaged in backcross breeding and genetic modification is essential to the restoration of the chestnut. But the success of TACF also has come from thousands of members and volunteers who have supported the work of the scientists. From the beginning, TACF understood the importance of engaging with people outside traditional scientific research circles to accomplish restoration.

People who mourned the past also supported work to bring about a future where the chestnut once again plays an important role in the ecosystems of the eastern woodlands. TACF members have been, per scientist Philip Rutter from the University of Minnesota, “trying to do something about the problem rather than just lament the loss,” which certainly challenges the argument that nostalgia can reduce the ability to act in the present.

While maybe not quite as tall or as wide as remembered in chestnut stories, the American chestnut tree occupied a significant place in the forest and in the lives of those who lived under its spreading branches—and it is certainly worthy of the work to restore it. Chestnut stories document this significant place chestnuts held in the forest ecosystem, and the sharing of the stories reminds people of the value the tree brought to Americans before the blight destroyed it. In an interview with Charles A. Miller, William Good remembers how farmers fattened their hogs off chestnuts: “In the fall, because people didn’t raise corn to feed their hogs, farmers would let them run in the mountain where they fattened up on chestnuts. The hogs would have to eat through the big burs on the outside to get the nut out. . . . The hogs must have liked the nuts so much they would chew through them until their mouths were bleeding.”

In an interview that appears in the 1980 folklore collection Foxfire 6 and is reprinted in TACF’s journal, Noel Moore recollects that people in the Appalachians did not build fences to keep their stock in; they instead fenced around their homes and fields to keep out the free-range stock wandering the woods. Each fall, farmers would round up and butcher their hogs that had grown fat on acorns and chestnuts. Chestnuts also served as an important food source for wild animals, including turkeys, black bears, white-tailed deer, gray fox squirrels, and the now extinct chestnut moth. These animals, in turn, fed those who hunted them. Chestnuts also were an important food source for people. Myra McAllister, who grew up in Virginia, recalls that she liked chestnuts “raw, boiled, and roasted by an open fire.” Cecil Clink, who grew up in North Bridgewater, Pennsylvania, remembers filling old flour sacks with the nuts, which his mother would store in the family’s “butry,” or buttery, “with the smoked hams. . . . [They ate] the nuts boiled, or put them on the cook stove and roast them.” Other people made stuffing and traditional Cherokee bread out of the nuts, though they could not grind the nuts into flour because they were too soft; the nuts had to be pounded by hand into flour instead. And it was not just the nuts themselves that people loved. Noel Moore remembers the taste of the honey that bees made from the chestnut blossoms. The leaves also had medicinal uses: the Mohegans made tea to treat rheumatism and colds, and the Cherokee made cough syrup.

Some stories recall the act of selling chestnuts, which gave many families cash that they might otherwise not have had—likely making it a memorable moment. In Where There Are Mountains, Donald Davis shares the chestnut story of John McCaulley, who as a young man had gathered chestnuts for sale. The nuts he gathered sold for four dollars a bushel in Knoxville, Tennessee—and McCaulley could gather up to seven bushels a day. Jake Waldroop remembers seeing wagons loaded with chestnuts in his northeast Georgia mountain community. The wagons headed to “Tocca, Lavonia, Athens, all the way to Atlanta, Georgia.”63 Noel Moore recalls seeing families coming from the mountains and heading to the store in the fall, laden with bags of chestnuts. They traded the bags for “coffee and sugar and flour and things that they had to buy to live on through the winter.”6 Exchanging chestnuts for supplies or cash was “much less risky than moonshining.”

To the north in Vittoria, Ontario, Donald McCall, whose father owned a store in the village, recollects that “farmers counted on the money from their chestnuts to pay taxes on the farm.” The trees themselves also had value. William B. Wood recalls that his father tried to save the family farm during the Great Depression by felling and selling the wood of a huge chestnut tree dead from the blight that Wood calls the “Chestnut Ghost.” Unfortunately, the plan did not work, and the family lost their farm.Other stories connect to the “usefulness” of the tree. Because chestnut wood is “even grained and durable . . . light in weight and easily worked,” the tree was used for a wide variety of purposes. Georgia Miller, who was 101 when she wrote “Chestnuts before the Blight,” recalls the split rail fences that lined the edges of pastures. The chestnut wood split easily and lasted longer than that of other species, making it a good material for what some called “snake fences.” Daniel Hallett, born in New Jersey in 1911, says his family used chestnut to trim doors and windows and also for chair rails in the houses they built. Dr. Edwin Flinn’s story (told by Dr. William Lord in 2014), which focuses on the extraction of tannins from dead chestnut trees, shows that the tree remained valuable even after the blight struck.

Chestnut stories recount more than memories of the tree’s usefulness or the role it played in Indigenous and rural economies. Many stories have documented how an encounter with the tree mobilized someone toward engagement with the restoration effort, demonstrating that chestnut stories can provide a pathway to a wider recognition of the natural world. Patrick Chamberlin describes such an experience in “A Practical Way for the Layman to Participate in Breeding Resistance into the American Chestnut.” Chamberlin tells readers how his grandmother used to reminisce about the tree when he was a young boy and then how he came across a burr from an American chestnut while in high school. He started looking for trees as he explored the woods on his parents’ farm. Eventually, while wandering near the old homestead site where his grandmother grew up, he came across two flowering chestnut trees. Returning later in the season, he found nuts from the trees. Through this experience, Chamberlin became involved in the back- cross breeding program—and, at the end of his essay, encourages others to do the same. A chestnut story from the distant reaches of his youth started him on his journey, and science helped him continue his work into the present. Fred Hebard, who directed TACF’s Meadowview Research Farms for twenty-six years, saw his first American chestnut sprout while helping round up an escaped cow with a farmer he worked for. When the farmer told him the story of the American chestnut, Hebard ended up changing his college major, earned a PhD in plant pathology, and began researching the chestnut. It became his life’s work.

Reprinted from Branching Out: The Public History of Trees. Copyright © 2025 by University of Massachusetts Press. Published by the University of Massachusetts Press.