German Radicals vs. the Slave Power

Bird’s Eye View of St. Louis, 1860. [The State Historical Society of Missouri]

In the late 1870s, the 70-year-old newspaper editor Henry Boernstein sat down to write about German immigrants’ efforts to shape the United States into a less brutal, more enlightened republic in the leadup to the Civil War. “When the microscopic loupe and the sharp analysis of criticism were applied to the Constitution and institutions of the United States,” Boernstein wrote in those memoirs, “one soon discovered that the republic and its constitution, in fact all American conditions, were a mass of incoherencies and contradictions.” He didn’t mince words: “The Constitution of the United States — which had been brewed up by a bunch of old fogies way back at the end of the last century with no notion whatsoever of modernity — was best to be altered in a contemporary way so as to conform with the relations and demands of the enlightened nineteenth century, particularly of the eternally venerated year 1848.”

More than a century later, the historian Steven Rowan translated Boernstein’s story, and Memoirs of a Nobody: The Missouri Years of an Austrian Radical, 1849-1866 was published for the first time in English in 1997. Rowan’s work on Boernstein (much of which is sadly out of print) helps explain how in the hell a European socialist helped found the now ultra-conservative Missouri Republican Party.

Boernstein’s era was full of apocalyptic omens, and far from being a “nobody,” Henry fits the Hegelian conception of the Hero in history — not a “great man” who imposes his will on events, but an individual who finds the Truth of the age, and defines what is ripe for development. “It was theirs to know this nascent principle,” Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel says in his Philosophy of History lectures, “the necessary, directly sequent step in progress, which their world was to take; to make this their aim, and to expend their energy in promoting it.” Sometimes, that step is taken in slippers, rifle in hand.

Born in Hamburg in 1805, Boernstein moved frequently throughout his teenage years after leaving behind a detested education under Jesuit schoolmasters. During five years in the Austrian military, he became disillusioned with the nobility’s pointless wars. He bounced between countries and a variety of professions, including acting, writing, journalism, and politics, with a streak of money-making business adventures mixed in. Boernstein eventually ended up the director of a German theater in Bohemian Paris just in time for the 1848 revolutions — a wave of democratic uprisings against Europe’s decrepit monarchies. He was, per Rowan, later regarded by some “as too old and too personally slippery to be a true ‘Forty-Eighter.’”

In the lead-up to the revolutions, Boernstein and a fellow journalist named Karl Ludwig Bernays began a liberal-reformist review of culture and politics titled Vorwärts!, or, Forward! The publication mostly reworked French plays for the German stage, and what little politics it held were in favor of a free press and against secret court proceedings. Nonetheless, Vorwärts! was banned from the mail in Germany, and subsequently lurched to the left. Boernstein and Bernays took on a group of argumentative socialists including Arnold Ruge, Friedrich Engels, and Karl Marx. Socialism in its infancy was “a matter of writing and talking, of scholarly research and speculation,” according to Boernstein, who adopted the newspaper’s new outlook with gusto — although he didn’t love that the paper’s offices were always full of guys “smoking like mad, debating with the greatest agitation and passion.”

Bernays eventually drew the ire of the French government after publishing an article praising an assassination attempt on King Frederick William IV. The Prussian government demanded the suppression of the journal, and as Rowan describes it, the French police “acted with special speed to close the paper.”

Historians frequently say the 1848 Revolutions “failed.” The struggles did not topple monarchs, or defenestrate archbishops, or execute princes. The idealistic communists and socialists who took up arms were cast from their continent, but in America, they arrived just in the nick of time. Between 1830 and 1854, German immigration increased ten-fold, with nearly 200,000 Germans migrating to the United States (a country of just 23 million), where many ended up in the Midwest.

Boernstein was among those who gravitated to the continent’s center. Like many immigrants, he was drawn in by Gottfried Duden’s popular Missouri travelogues, which pointed to the Midwest’s many Rhineland-esque qualities, including enriched soil from the many confluences of rivers, as well as “temperate” weather. The advertising proved to be a little false when Boernstein arrived in the sticky and pandemic-friendly humidity of St. Louis in 1849. The city was vulnerable to cholera due to its primitive and often nonexistent sewer system. Water that came out of spigots “had an alarming appearance,” Boernstein wrote, noting the strategy of letting a glass sit for 15 minutes before taking a sip, so as to let the muck sink to the bottom.

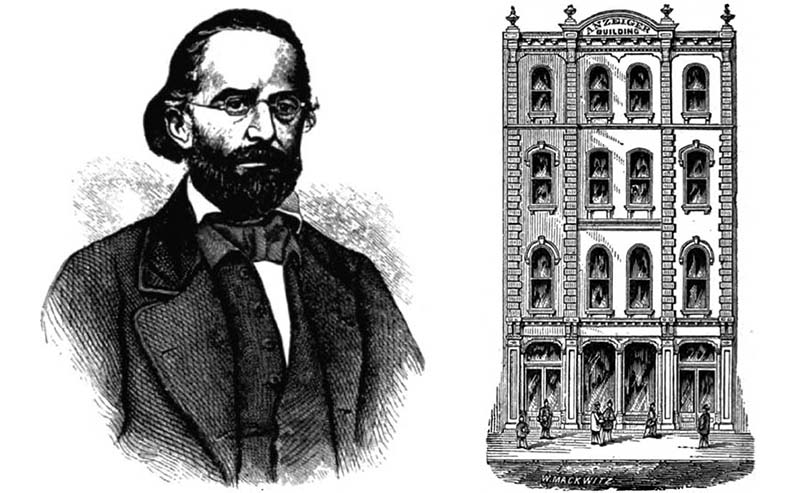

Cholera killed 10% of the city’s residents in 1849. The great St. Louis fire broke out on May 19, only exacerbating the horrors. Boernstein briefly fled the madness with his wife Marie to start a health spa in Highland, Illinois, but a fancy job offer lured him back to St. Louis less than a year later. He was back editing, tasked with reviving the subscription base of the Anzeiger des Westens — the “Gazette of the West.”

Boernstein was not exactly clear on what had happened in American history up to that point, and his learning curve was steep. He had been hired because of his experience in European papers, but as he admitted, “at that time I had not yet grasped the full importance of the slavery question.” While getting his bearings, Boernstein complained that locals on all sides of the issue would sit in his office for hours “chewing tobacco, spitting in my stove, and talking me to death.”

The U.S. political options were not great for Boernstein’s readers in the 1850s. They could vote for the nativist Whigs, who wanted immigrants oppressed and deported, or the pro-slavery Democrats, who were bought and paid for by the Slave Power — owners and operators of the vast system of chattel slavery. The only good news was that the two major parties were dying, and change was being forced on the United States by the admission of new states, like Kansas and Nebraska, to the Union. Both parties were moribund — the U.S. was packed with immigrant communities who opposed the nativists, and the Slave Power had installed pro-slavery politicians in every level of government who were steering the country toward a Southern secession, and therefore the party’s death by exile.

In Missouri, an oddball third faction developed around Senator Thomas Hart Benton. Though Benton owned slaves himself, he and the “Benton Democrats” opposed the expansion of slavery, which undercut the power of free labor on railroad construction and other expansionist projects. As Benton rose to prominence, Boernstein used his newspaper to rally fellow Germans to this cause, nurturing a politics that would eventually develop into Lincoln Republicanism.

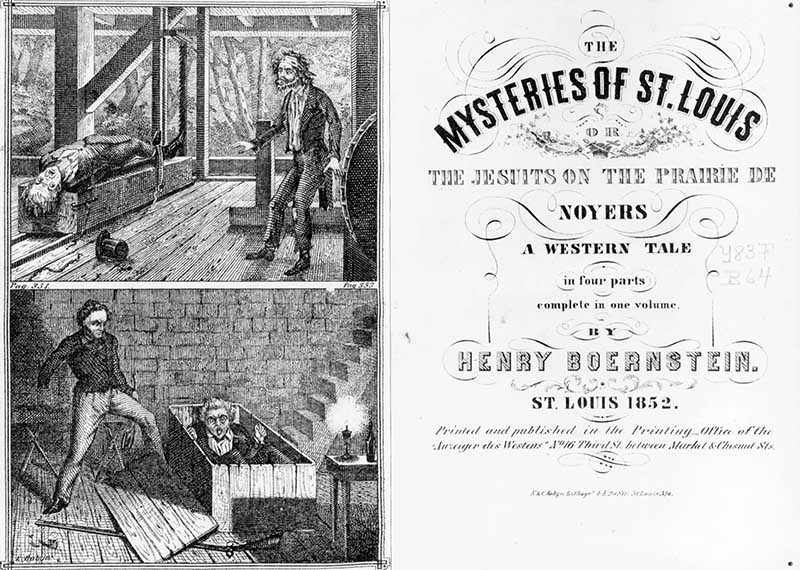

In 1851, Boernstein began serializing his first and only novel in the Anzeiger. It was the first novel ever set in St. Louis. The title, The Mysteries of St. Louis, was meant to evoke a popular series of melodramatic, French-style novels with conspiracy plots. Boernstein’s book revolved around a buried treasure at the Prairie de Noyers — a western tract of land between Grand Avenue and Kingshighway where the Jesuit-run St. Louis University now sits. The treasure is part of a Jesuit conspiracy to overthrow the United States government in favor of Vatican rule. Villains in Mysteries are both clerics and capitalists depicted as preying upon moral, innocent, hard-laboring workers — German readers were eager to learn anything about the New World, warts and all, and St. Louis readers found under-discussed predatory conditions laid bare and lampooned. The English translation of Mysteries, published in 1852, is affectionately dedicated to Thomas Hart Benton. In his memoirs, Boernstein recalled a queasy dinner at Benton’s house — a building that was empty while Benton was in Washington, DC, and that became so full of mice that a few ended up on Boernstein’s lap during the meal, which he and a friend thought was very funny. Mysteries reads much like Boernstein’s first-hand experiences of St. Louis, and helped him win over his German readership. As Boernstein put it, it made him “the political and social leader of my compatriots, who honored me with their trust and depended upon me.”

Most German immigrants in 1850s St. Louis were antislavery free-soilers, meaning they opposed slavery because it competed with white labor. But in his memoirs, Boernstein identified a generational split among them. An older set was “mocked as ‘Grays,’” and had immigrated seeking economic opportunity, sometimes looking down on peasant German immigrants, “with their caps, their long pipes, their sauerkraut and beer.” Then there were the newer “Greens,” named for their inexperience, who had fled European tyranny to find themselves in a new land. Many of the Greens were Forty-Eighters much less interested in U.S. politics than in plotting to assassinate princes back in Baden. They saw themselves as biding their time in America before a revolutionary return to Germany, where they would inaugurate a new republic. The Greens were often impressively educated; some were lecturers at German academies who came to St. Louis and found work as waiters or stable hands.

Considering his age, politics, and role as a businessman, Boernstein was a mix of both Gray and Green. He used the Anzeiger to unite both factions into a coherent bloc of German American voters. The Hegelian Truth of Boernstein’s age was that slavery, and the oligarchical Slave Power, was not only an ongoing moral atrocity — it was also tearing the country apart, dooming the United States to a future of schism and unchecked capital exploitation. Articles in the Anzeiger encouraged the Greens to give up distant hopes for revolution abroad when there were problems to fix here and now in their new home. To the Grays, the Anzeiger argued that a unified German political voice was the only thing that would cut through both the Slave Power and the nativists. “They would have to avoid all division over secondary matters and gather themselves in unity behind their chosen leaders,” Boernstein wrote. This big tent effort worked. “They began to count their own number and realized their strength if they would only unite.” By the mid-1850s, the St. Louis Germans began to organize as a militant political force; first around the right to drink beer on Sundays, then around the issue of slavery.

As the U.S. became more corrupted by the monied interest of slaveholders, a movement against the Slave Power was becoming an easier sell. “Congress required every citizen to catch escaped slaves and return them to their proper owners,” Boernstein wrote. “Where these laws did not suffice, brutal force was applied,” with opponents “assaulted by mobs, their property destroyed … expelled from the state, mishandled, murdered.” The Anzeiger printing offices were targeted for the newspaper’s antislavery stance, and nativists were always threatening to set the German neighborhoods aflame. Boernstein brushed them off as “silly threats.” In 1854, St. Louis elected a nativist mayor named Washington King, and in the process, provoked a giant nativist riot that suppressed the German vote. Boernstein was first on the kill-list alongside Frank P. Blair, who “merit being called the founders of the Republican Party in the slave state of Missouri,” Boernstein proudly declared.

Eventually, Boernstein had to put down the pen and pick up a different kind of weapon. At the start of the war, the largest stockpile of guns, ammunition, cannons, and military equipment west of the Mississippi was near downtown St. Louis. “If this arsenal had fallen into the hands of the secessionists,” Boernstein wrote, exaggerating a little, “then the western free states of Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Wisconsin, and others would have remained entirely unarmed.”

President James Buchanan’s war secretary had been emptying Northern arsenals and sending weapons to military fortifications in the South. In April 1861, a mob of Confederates seized the arsenal in Liberty, the only other federal cache in Missouri. Controlled by many pro-Confederates, the Missouri government in Jefferson City was unable to muster complete succession, but took control of the St. Louis Police Department. Officers set about harassing anti-slavery Germans, shutting down beer gardens as well as Boernstein’s passion project, the St. Louis Opera House. However, the St. Louis arsenal remained in control of Union officials.

A Confederate militia camp named after pro-slavery Missouri Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson sprang up on the western hill overlooking St. Louis, where secessionists began to drill and eye the downtown arsenal. To pay for the militia stationed there, Boernstein wrote, “which was to join the Southern secessionist army, the funds of the public schools, madhouses, and houses of the blind were seized, and through this mean act of violence 10,000 schoolchildren in St. Louis alone were thrown out of their intuitions of learning into the streets.”

Camp Jackson, full of the gun-toting sons of the St. Louis rich, was not a threat in itself, but Confederate troops from the hinterlands of Missouri threatened to reinforce the position and sack the city. At one point, the Confederate rich kids tried to capture the downtown arsenal, but had to go through the German wards first. They were yelled at in the streets, grew scared, and turned tail.

Union General Nathaniel Lyon was stationed in Missouri, and did not have enough enlisted troops to fortify and defend the arsenal forever. He was a Know Nothing nativist who hated Germans, but German militiamen were all he had, and he met with local leaders, including Franz Sigel, Frank Blair, and Boernstein, to organize them. The St. Louis Turner Society, an all-in-one philosophical group, bar, and shooting club, was full of Forty-Eighter veterans with combat experience against royal European shock troops. German militia groups began drilling along with the Turners, and Boernstein dusted off his military training to head up a volunteer company.

On April 23 — days after the attack on Fort Sumter that kicked off the Civil War — the crypto-secessionist army brigadier based in St. Louis left town, freeing General Lyon to frantically muster the German militia to the arsenal. Brigadier General William S. Harney — the murderer of a slave woman named Hannah — was the final impediment to the German revolt. “We had marched in such haste that I had not even found time to put on my boots,” Boernstein wrote, “so that I performed my first military expedition in my slippers. I only lacked my dressing gown to make it complete. Thank heavens I had quit wearing a dressing gown in those troubled times, and I was fortunate that it was a dark night and no one saw my slippers.”

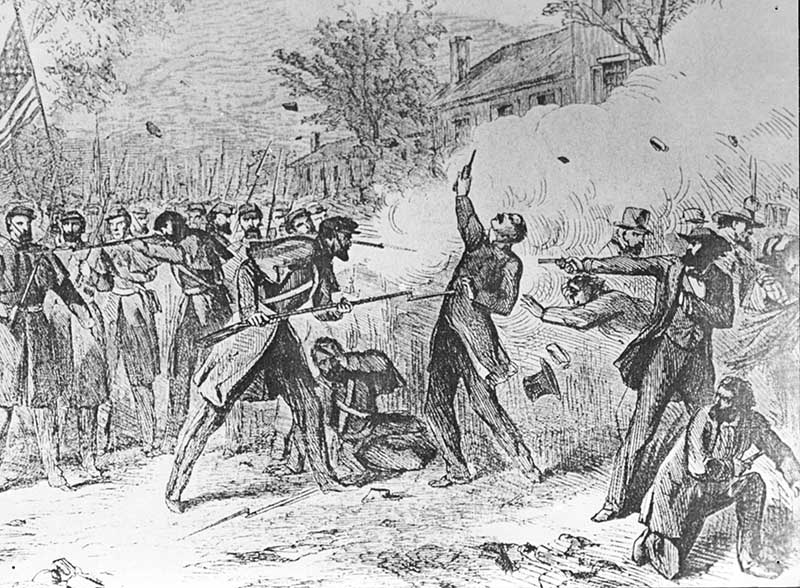

On May 10, General Lyon marched every soldier under his command out of the arsenal — around 6,000 in three columns — and crossed the city of St. Louis to the western ridge. Many in the enemy encampment had seen the writing on the wall, and the fortification lay semi-deserted. Camp Jackson was overwhelmingly surrounded, and 669 Confederates were taken prisoner. While the Confederate militia was largely absent, a mob of sympathetic and curious St. Louisans turned out to challenge what they called “cheap Hessian mercenaries” in a “street battle.” It was Boernstein’s troops who were fired upon at Camp Jackson, and who first fired back. Around 28 civilians were killed and more than 75 wounded.

The next day, Boernstein gave his men permission to go see their families. “Most of them did not return,” he writes, “until it grew dark, with clothing torn, faces beaten bloody, and all the signs of having suffered mistreatment … Two of them never returned, and they were never heard of again. It is probable that they were beaten to death and their corpses thrown in the river.”

After Camp Jackson, General Lyon captured Jefferson City and began hunting down the Confederate troops elsewhere in Missouri. Boernstein was left behind in the state capital to serve the daunting job of occupational commander. He used his theater skills to create the illusion that the state capital was well-defended by many troops, when in fact the Union forces were spread very thin. After his three months of military service, the Lincoln administration rewarded Boernstein with a position back in Europe, heading up a German consulate. He spent the next few months reading bad news about the Union under General George B. McClellan, and listening as Europeans got ready to negotiate new trade deals with Jefferson Davis’ Confederacy.

Then Lincoln emancipated the slaves, Grant trounced Robert E. Lee, William Tecumseh Sherman burned the South from Atlanta to Savannah, and the slaveholders were very briefly scattered to history — right before being welcomed back into U.S. civic life in different guises. Some ex-Confederates took Ironclad Oaths, others offered some apology, but many more remained stalwart pro-slavery racists and continued shaping American civil life.

But for a moment, Boernstein celebrated — he threw a big party in the German consulate, complete with red, white, and blue bunting. He had been right to risk his life and livelihood for the cause of democracy, and it’s not a stretch to say that his coalition of Germans helped to abolish slavery. At the outset of the Civil War, it seemed to many that a far more likely outcome would be stalemate. Had the West fallen to the secessionists, with St. Louis, Chicago, Milwaukee, and Cincinnati lacking their antislavery German populations, Southern independence might have been unavoidable.

As Boernstein said, the constitution was written by old fogies, but 13th Amendment improved the document. The risks had been worth it, though the coalition of Germans in St. Louis fractured after the war. The United States became a slightly freer country with a long way to go, in large part thanks to its German immigrants.