On a Hunt for 19th-Century Erotica, We Found Lesbians

If it wasn’t clear from the headline, this essay explores sexually explicit themes, and includes images that may not be fit for workplace viewing. Alexandra Vasti’s research anchors the first part of the piece, before passing the perspective to Raisa Rexer.

In 1748, John Cleland published Fanny Hill and initiated the tradition of the erotic novel in English. Fanny Hill, or Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, tells the story of teenage Fanny, who, over the course of the novel, joyfully embarks upon a life of sin, falls for a nice young man, has erotic adventures in and on every imaginable surface, and eventually lives happily ever after.

Fanny’s first few sexual encounters, however, are with another woman.

Lying cozily in bed with her brothel roommate Phoebe, Fanny is surprised but willing to be introduced to the “strange, and, till then, unfelt pleasure” aroused by Phoebe’s “lascivious touches.” In the subsequent days, Fanny turns to Phoebe with various questions — and asks for demonstrations — as she witnesses sex acts in the brothel. When she becomes aroused, Fanny asks Phoebe for aid, and the two women repeatedly bring each other sexual satisfaction until Fanny begins to “pine for more solid food” — that is to say, a phallus — and decides to leave off “this foolery of woman to woman.” Phoebe, for her part, seems to be what we would today call bisexual. She is “inclined … to make the most of pleasure wherever she could find it, without distinction of sexes.” Other women in the novel specifically and exclusively pursue lesbian sex.

The first time I read Fanny Hill, I was startled by such frank depictions. I was deep in the research process for my first historical romance novel, Ne’er Duke Well, in which our heroine creates a library for the purpose of women’s sexual education. To properly fill out her catalog with real 18th- and 19th-century texts, I decided to embark upon a project of reading all sorts of educational books, from pseudo-medical treatises such as Aristotle’s Masterpiece to erotica. Fanny Hill’s immense fame and popularity made it the first 18th-century erotic novel I read, but not the last.

The earliest form of the erotic novel can be seen in dialogues such as Venus in the Cloister (first published in 1683 and expanded in 1702 and 1719) and The School of Venus (first edition 1680, second edition 1728). Both of these works were originally published in French and then quickly translated into English, where, in the 18th century, they were relatively available for the general reading public. In London, Holywell Street was a hotbed of obscene prints sold within the context of average bookstores; not until the Vagrancy Act of 1824 was erotic publication forced into a more clandestine (but still widely practiced) trade. And while the Victorian era in England saw erotica move increasingly underground, obscenity laws were generally looser in France. One of the quirks of French law in the 1850s and 1860s was that it was possible to sell nude images without fear of prosecution if they were approved by the government in advance.

Across this spectrum of erotic words and images, sapphic sex can be found just about everywhere.

Often, these sexual encounters between women are framed as educational. In Venus in the Cloister, an older nun instructs a younger nun in masturbation, followed by a variety of other sexual acts. Not atypically for the period, these sexual interludes alternate with thoughtful dialogues on the “many abuses practiced in our religion,” the relationship between Church and State, and the hypocrisy of “dissolute” leaders who attempt to use religion as a tool for control. In The School of Venus, an older, married woman decides to assist her cousin’s pursuit of a younger woman by seducing the other woman and thus preparing her for her future heterosexual adventures.

In these erotic works, lesbian sex is, perhaps unexpectedly, normalized. Phoebe’s desire for Fanny is surprising to Fanny but not unwelcome — and Fanny recognizes immediately that some women might prefer to have sex with other women. Depictions of real-life “sapphists” in the period aren’t hard to find, either — a historical reality that serves as the background for my new Regency romance Ladies in Hating, a Northanger Abbey-inspired romp about a pair of rival Gothic novelists. A satirical cartoon printed in 1820 called “Love-a-la-mode, or Two Dear Friends” shows Louisa, Lady Strachan, and Sarah, Lady Warwick, kissing on a park bench while their husbands sulkily watch from the bushes. Regency sculptor Anne Seymour Damer (1748-1828) was so well-known for her female romantic entanglements that a lady suspected of lesbian leanings might be said to have “visited Mrs. Damer.” Diarist Anne Lister declared in 1821: “I love & only love the fairer sex & thus beloved by them in turn my heart revolts from any other love than theirs.”

And yet, despite these real-life examples, representations of lesbian sex acts in erotica are commonly dismissed as purely pornographic by academics and historians. Art historian Abigail Solomon-Godeau, for example, argues in her book Photography at the Dock (1991) that photographic images of women engaged in sex cannot “illustrate lesbian sexuality” because their “erotic display” must be read as “for the presumed male viewer.”

Discovering whether these texts can or should be read as representations of real 18th-century lesbian desire, and not some invention of the male gaze, requires some historical investigation. For more on this topic, I turned to my friend Dr. Raisa Rexer, who studies the early history of nude photography in France.

In 1839, the French government patented the daguerreotype process, making it public and available to anyone who wanted to take up photography. The process was time consuming, expensive, and yielded a single image. Yet even with these barriers, people almost immediately began to take nude photographs. Those nudes included images of women that were, if not explicitly lesbian, certainly lesbian-coded, with women depicted naked together or mid-caress.

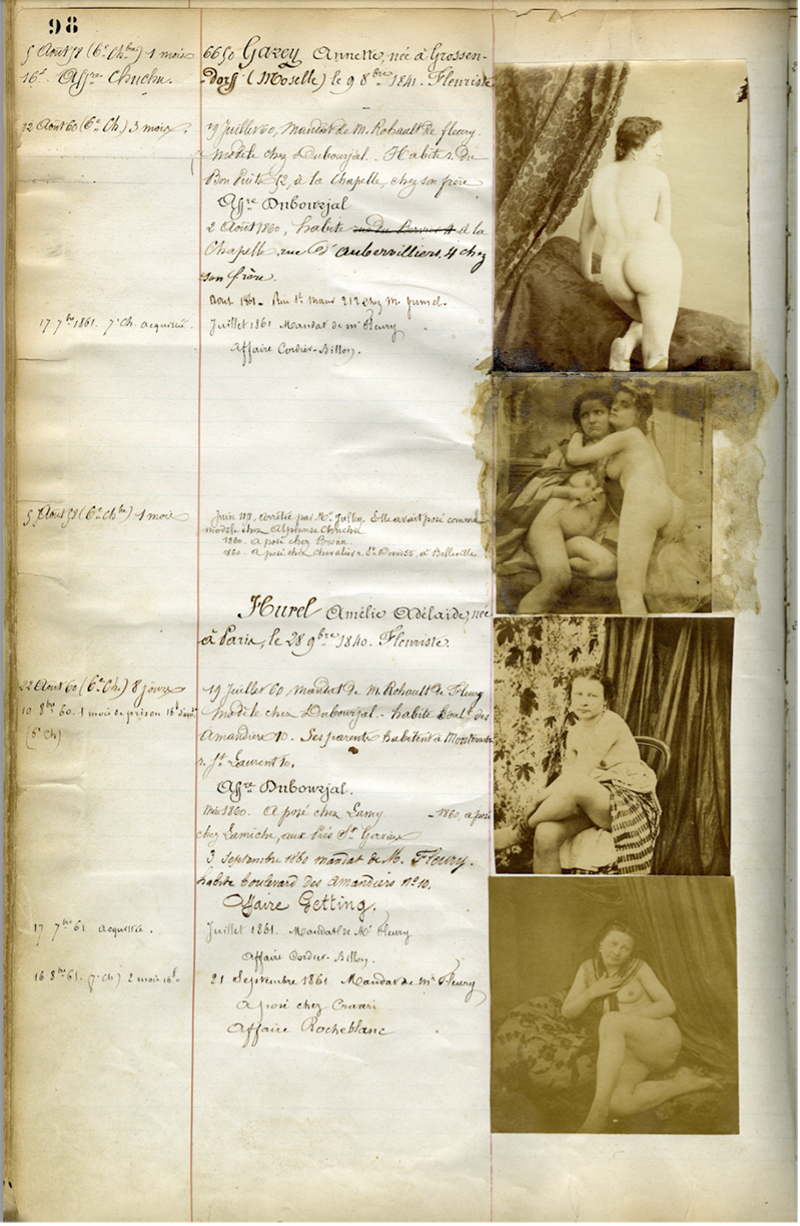

Daguerreotype nudes of all kinds, but particularly of lesbians, are very rare today. Not so with photographic nudes from several years later. By the 1850s, technological advances allowed photographers to produce multiple, inexpensive paper prints from a single negative, often as double stereograph images (which appear in 3-D through special viewers) or as small calling-card sized cartes-de-visite. These developments led to an explosion in the popularity of photography, and, inevitably, the spread of nude images. Because such images were bought and sold clandestinely, it is hard to say with certainty how many nude and erotic images were produced and sold in France in the mid-19th century. In the 1850s and 1860s, police raids yielded hundreds or thousands of images at a time, suggesting circulation in the tens or hundreds of thousands.

It is even more difficult to say exactly how much of this erotica featured lesbian imagery. But there are enough examples in the police records to indicate that with the proliferation of photography in general, lesbian-coded imagery also became more readily available. Moreover, lesbian imagery was not confined to the realm of illegality. In addition to the lesbian images that appear among the photos seized during police investigations, examples also exist of sexually suggestive photographs of nude women that were authorized by the government and sold legally as “art studies.”

By the early 1890s, thanks both to technological advances and the repeal of France’s harsh censorship laws, the number of photographic nudes in circulation exploded again from the thousands to the millions; in 1892, a single commercial photographer was arrested who had managed to distribute some 800,000 explicit photographs in under three years. Until the 1880s, nude photographs would have had to have been taken by professional photographers with the necessary studio space and equipment. Some of them, especially the daguerreotypes, might have been private commissions, but most were produced for commercial sale and consumption. As photographic technology changed, people no longer had to purchase their erotica from photographers. The invention of the Kodak and other personal cameras in the 1880s allowed people to take up photography as an individual — and private — hobby. Unsurprisingly, one popular use for early personal cameras was photographing nudes.

A series of albums created by an unnamed amateur photographer in Bordeaux between 1889 and 1910, now housed in the Enfer of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, offers a glimpse of the lesbian erotica that circulated at this time. These photographs depict groups of women in what is very likely a brothel and are far more explicit than the commercial images from the 1850s and 1860s. Women masturbate. They perform oral sex on each other; they play with dildos; they give and receive pleasure.

Above all, the photographs showcase women enjoying their bodies without a male presence.

(One of the photographer’s three albums can be found here. Please be aware, it contains sexually explicit images.)

These works invite us to consider the complicated gendered relationship between subject, producer, and consumer.

The reality is that most 19th-century photographers and pornographers were men, producing commercial nudity for a male audience. That is not to say that no women took erotic photographs or derived pleasure from them. To make that claim would be to write women and their desires — sapphic or otherwise — out of history. Indeed, we see in Anne Lister’s diaries that she was familiar with texts that frankly depicted female anatomy: After “studying the female organs of generation” in a book, she finds her own sexual practices more satisfying.

We have no way of knowing who was behind the personal cameras of the late 19th century, why they made nude photographs, or for whom they were intended. But even in the earlier era of professional photography, it can be dangerous to make gendered assumptions. Raisa is currently working on the biography of Laure-Mathilde Gouin, a woman photographer who has been written out of photographic history. Gouin was taking nudes as early as the 1850s, but her photographs were all posthumously attributed to her husband and father, illustrating exactly the erasure that we are working to correct.

In our (very different!) work, we both argue for a reclamation of female agency, particularly in the context of 19th-century sex and sexuality. There is no reason to assume depictions of lesbians never reflected real, lived sexual desires. Though the explicit photographs in the Enfer of the Bibliothèque nationale de France are clearly staged — just as Phoebe’s sexual desire for Fanny is a fictional account — they nonetheless represent the real world of 18th- and 19th-century Britain and France: a world in which sapphic desire is presented as one of many possible modes of giving and receiving pleasure.