A. Philip Randolph Lambasts the Old Crowd

“The New Negro” is one of the oldest, longest serving, and most fascinating concepts in the history of African American culture. Expansive and elastic, capable of morphing and absorbing new content as circumstances demand, contested and fraught, it assumes an astonishingly broad array of ideological guises, some diametrically opposed to others. The New Negro functions as a trope of declaration, proclamation, conjuration, and desperation, a figure of speech reflecting deep anguish and despair, a cry of the disheartened for salvation, for renewal, for equal rights.

While most of us first encounter the “New Negro” as the title of the seminal anthology that Alain Locke published in 1925, at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, we find the origin of the term — so closely associated by scholars and students alike with the multihued cacophony of the Jazz Age — actually goes back to 1887, four years after the U.S. Supreme Court had voided the liberal and forward-looking Civil Rights Act of 1875, thereby declaring with ultimate finality the end of Reconstruction. This was a time of great despair in the African American community, especially among the elite, educated, middle and upper middle classes. How to fight back? How to regain the race’s footing on the path to full and equal citizenship? This is how and when the “New Negro” was born, in an attempt to find a way around the mountain of racist stereotypes being drawn upon to justify the deprivation of Black civil rights, the disenfranchisement of Black men, and the formalization of Jim Crow segregation, all leading to the onset of a period of “second-class citizenship” that would last for many decades to come — far longer than any of the first New Negroes could have imagined.

One member of the New Negro coalition was A. Philip Randolph (1889-1979), a Black socialist and labor organizer hailed by Martin Luther King Jr. as “truly the Dean of Negro Leaders.” Immediately attracted to socialism as the best means of addressing the systemic exploitation of Black workers, he joined the Socialist Party with Columbia University student Chandler Owen. The two started giving soapbox speeches and founded the socialist Messenger magazine in 1917, which they proclaimed offered readers “the only magazine of scientific radicalism in the world published by Negroes!” Even before founding the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids in 1925 and making the Messenger the union’s official organ, Randolph used the idea of the New Negro repeatedly as a call to action. Indeed, the Messenger cast out the previous era’s New Negroes as old and unable to address the crisis of the Red Summer.

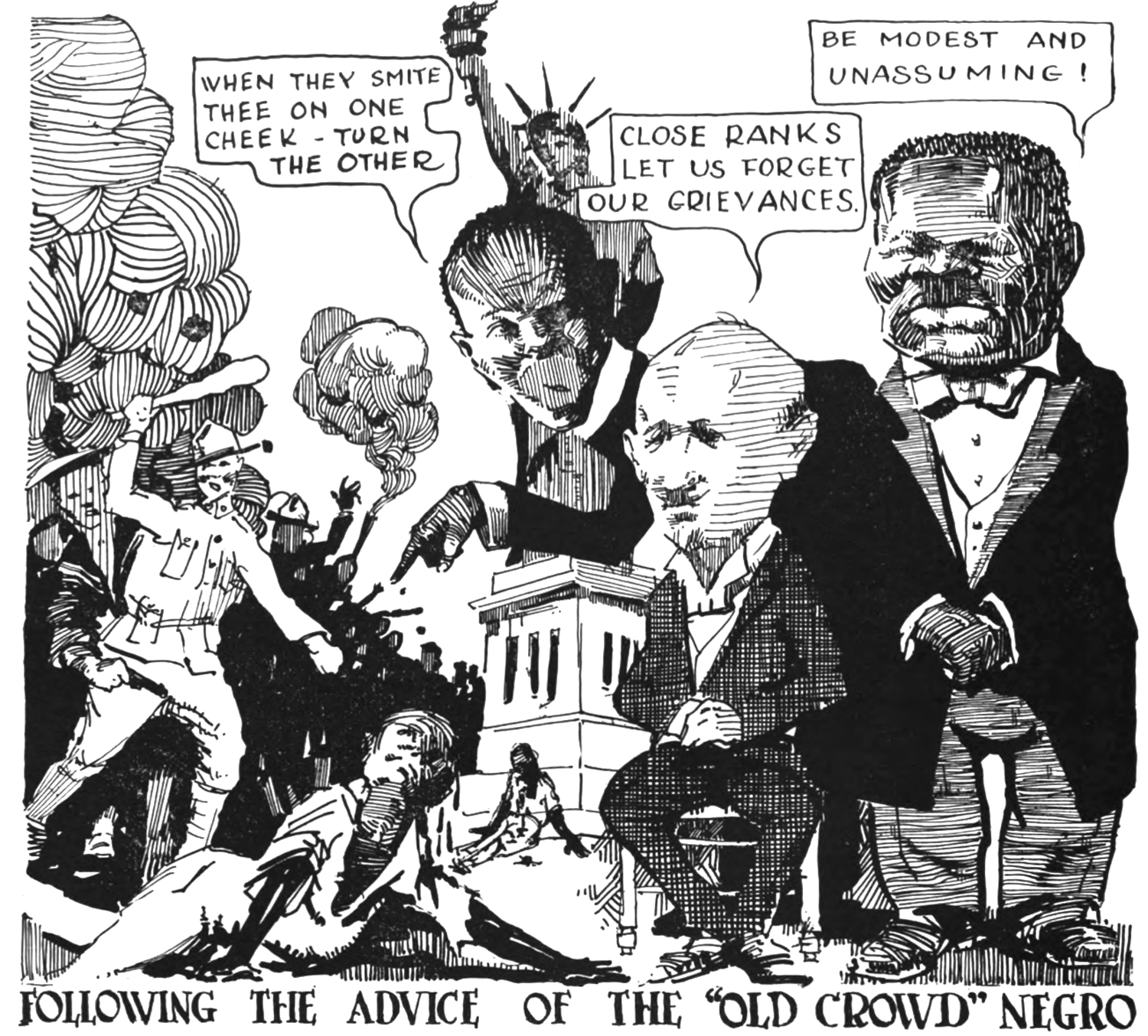

In the September 1919 issue, the Messenger included a half-page satirical political cartoon, “Following the Advice of the ‘Old Crowd’ Negroes,” that featured Du Bois, Robert Russa Moton (the successor to Booker T. Washington at the Tuskegee Institute after Washington died in 1915), and Emmett Jay Scott, secretary to Moton and a close adviser of Washington. On the left side of the cartoon a white man in military uniform leads a jeering, torch-carrying mob, and wields a club to attack an already bloodied Black person who struggles to raise from the ground. Another bloodied Black victim sits propped up at the base of the Statue of Liberty. On the night of July 18, 1919, in Washington, DC, over one hundred white servicemen, a “mob in uniform,” wielded pipes, clubs, rocks in handkerchiefs, and pistols attacking Black people they saw on the street. The Black historian Carter G. Woodson, in fact, fled the mob on foot.

In the cartoon, three august “Old Negroes” propose accommodationist responses to the violence. A seated Du Bois implores, close ranks let us forget our grievances, a reference to his famous Crisis editorial the previous year urging Black readers to support World War I. Beside him, with hands clasped, stands Moton, who urges, be modest and unassuming! Scott, reaching back to Moton, says, when they smite thee on one cheek—turn the other.

“The ‘New Crowd Negro’ Making America Safe for Himself,” features a clearly younger New Negro veteran in a speeding roadster — labeled the new negro, equipped with guns firing in the front and sides, and displaying a banner commemorating infamous 1919 sites of race riots, “Longview, Texas, Washington, D.C., Chicago, ILL.—?” As he fires at the fleeing white mob, a fallen member of which is in uniform, he declares, since the government won’t stop mob violence ill take a hand. In the clouds of smoke appears the caption giving the ‘hun’ a dose of his own medicine. Above, the editors quote Woodrow Wilson’s April 1918 Great War rallying cry against Germany: force, force to the utmost—force without stint or limit! Clearly, socialism, for Randolph, offered New Negroes the organizational fighting power Black people needed to fend off the most symbolically treacherous of all white mob attacks — those by U.S. military servicemen in uniform.

In “Who’s Who: A New Crowd—A New Negro,” published in the May-June 1919 issue of the Messenger, in the wake of the Great War, Randolph urges Black socialists to join forces with white radicals and labor organizers to usher in a new era of social justice.

—Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Martha H. Patterson

Throughout the world among all peoples and classes, the clock of social progress is striking the high noon of the Old Crowd. And why?

The reason lies in the inability of the old crowd to adapt itself to the changed conditions, to recognize and accept the consequences of the sudden, rapid and violent social changes that are shaking the world. In wild desperation, consternation and despair, the proud scions of regal pomp and authority, the prophets and high priests of the old order, view the steady and menacing rise of the great working class. Yes, the Old Crowd is passing, and with it, its false, corrupt and wicked institutions of oppression and cruelty; its ancient prejudices and beliefs and its pious, hypocritical and venerated idols.

It’s all like a dream! In Russia, one-hundred and eighty million of peasants and workmen—disinherited, writhing under the ruthless heel of the Czar for over three hundred years, awoke and revolted and drove their hateful oppressors from power. Here a New Crowd arose—the Bolsheviki, and expropriated their expropriators. They fashioned and established a new social machinery, the Soviet—to express the growing class consciousness of teaming millions, disillusioned and disenchanted. They also chose new leaders—Lenin and Trotsky—to invent and adopt scientific methods of social control; to marshal, organize and direct the revolutionary forces in constructive channels to build a New Russia.

The “iron battalions of the proletariat” are shaking age-long and historic thrones of Europe. The Hohenzollerns of Europe no longer hold mastery over the destinies of the German people. The Kaiser, once proud, irresponsible and powerful; wielding his sceptre in the name of the “divine right of kings,” has fallen, his throne has crumbled and he now sulks in ignominy and shame—expelled from his native land, a man without a country. And Nietzsche, Treitschke, Bismarck, and Bernhardi, his philosophic mentors are scrapped, discredited, and discarded, while the shadow of Marx looms in the distance. The revolution in Germany is still unfinished. The Eberts and Scheidemanns rule for the nonce; but a New Crowd is rising. The hand of the Sparticans must raise a New Germany out of the ashes of the old.

Already, Karolyi of the old regime of Hungary, abdicates to Bela Kun, who wirelessed greetings to the Russian Federated Socialist Soviet Republic. Meanwhile the triple alliance consisting of the National Union of Railwaymen, the National Transport Workers’ Federation and the Miners’ Federation, threaten to paralyze England with a general strike. The imminence of industrial disaster hangs like a pall over the Lloyd George government. The shop stewards’ committee or the rank and file in the works, challenge the sincerity and methods of the old pure and simple union leaders. British labor would build a New England. The Sein Feiners are the New Crowd in Ireland fighting for self-determination. France and Italy, too, bid soon to pass from the control of scheming and intriguing diplomats into the hands of a New Crowd. Even Egypt, raped for decades prostrate under the juggernaut of financial imperialism, rises in revolution to expel a foreign foe.

And the natural question arises: What does it all mean to the Negro?

First it means that he, too, must scrap the Old Crowd. For not only is the Old Crowd useless, but like the vermiform appendix, it is decidedly injurious, it prevents all real progress.

Before it is possible for the Negro to prosecute successfully a formidable offense for justice and fair play, he must tear down his false leaders, just as the people of Europe are tearing down their false leaders. Of course, some of the Old Crowd mean well. But what matter is [it] though poison be administered to the sick intentionally or out of ignorance. The result is the same—death. And our indictment of the Old Crowd is that: it lacks the knowledge of methods for the attainment of ends which is desires to achieve. For instance the Old Crowd never counsels the Negro to organize and strike against low wages and long hours. It cannot see the advisability of the Negro, who is the most exploited of the American workers, supporting a workingman’s political party.

The Old Crowd enjoins the Negro to be conservative, when he has nothing to conserve. Neither his life nor his property receives the protection of the government which conscripts his life to “make the world safe for democracy.” The conservative in all lands are the wealthy and the ruling class. The Negro is in dire poverty and he is no part of the ruling class.

But the question naturally arises: who is the Old Crowd?

In the Negro schools and colleges the most typical reactionaries are Kelly Miller, Moton and William Pickens. In the press Du Bois, James Weldon Johnson, Fred R. Moore, T. Thomas Fortune, Roscoe Conkling Simmons and George Harris are compromising the case of the Negro. In politics Chas. W. Anderson, W. H. Lewis, Ralph Tyler, Emmet Scott, George E. Haynes, and the entire old line palliating, me-to-boss gang of Negro Republican politicians, are hopelessly ignorant and distressingly unwitting of their way.

In the church the old crowd still preaches that “the meek will inherit the earth,” “if the enemy strikes you on one side of the face, turn the other,” and “you may take all this world but give me Jesus.” “Dry Bones,” “The Three Hebrew Children in the Fiery Furnace” and “Jonah in the Belly of the Whale,” constitute the subjects of the Old Crowd, for black men and women who are overworked and under-paid, lynched, jim-crowed and disfranchised—a people who are yet languishing in the dungeons of ignorance and superstition. Such then is the Old Crowd. And this is not strange to the student of history, economics, and sociology.

A man will not oppose his benefactor. The Old Crowd of Negro leaders has been and is subsidized by the Old Crowd of White Americans—a group which viciously opposes every demand made by organized labor for an opportunity to live a better life. Now, if the Old Crowd of white people opposes every demand of white labor for economic justice, how can the Negro expect to get that which is denied the white working class? And it is well nigh that economic justice is at the basis of social and political equality.

For instance, there is no organization of national prominence which ostensibly is working in the interest of the Negro which is not dominated by the Old Crowd of white people. And they are controlled by the white people because they receive their funds—their revenue—from it. It is, of course, a matter of common knowledge that Du Bois does not determine the policy of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; nor does Kinckle Jones or George E. Haynes control the National Urban League. The organizations are not responsible to Negroes because Negroes do not maintain them.

This brings us to the question as to who shall assume the reins of leadership when the Old Crowd falls.

As among all other peoples, the New Crowd must be composed of young men who are educated, radical and fearless. Young Negro radicals must control the press, church, schools, politics and labor. The condition for joining the New Crowd are: equality, radicalism and sincerity. The New Crowd views with much expectancy the revolutions ushering in a New World. The New Crowd is uncompromising. Its tactics are not defensive, but offensive. It would not send notes after a Negro is lynched. It would not appeal to white leaders. It would appeal to the plain working people everywhere. The New Crowd sees that the war came, that the Negro fought, bled and died; that the war has ended, and he is not yet free.

The New Crowd would have no armistice with lynch-law; no truce with jim-crowism, and disfranchisement; no peace until the Negro receives complete social, economic and political justice. To this end the New Crowd would form an alliance with white radicals such as the I.W.W., the Socialists and the Non-Partisan League, to build a new society—a society of equals, without class, race, caste or religious distinctions.

Excerpted from The New Negro: A History in Documents, 1887-1937. Copyright © 2025 by Martha H. Patterson and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.