The Bad Bunny Doctrine

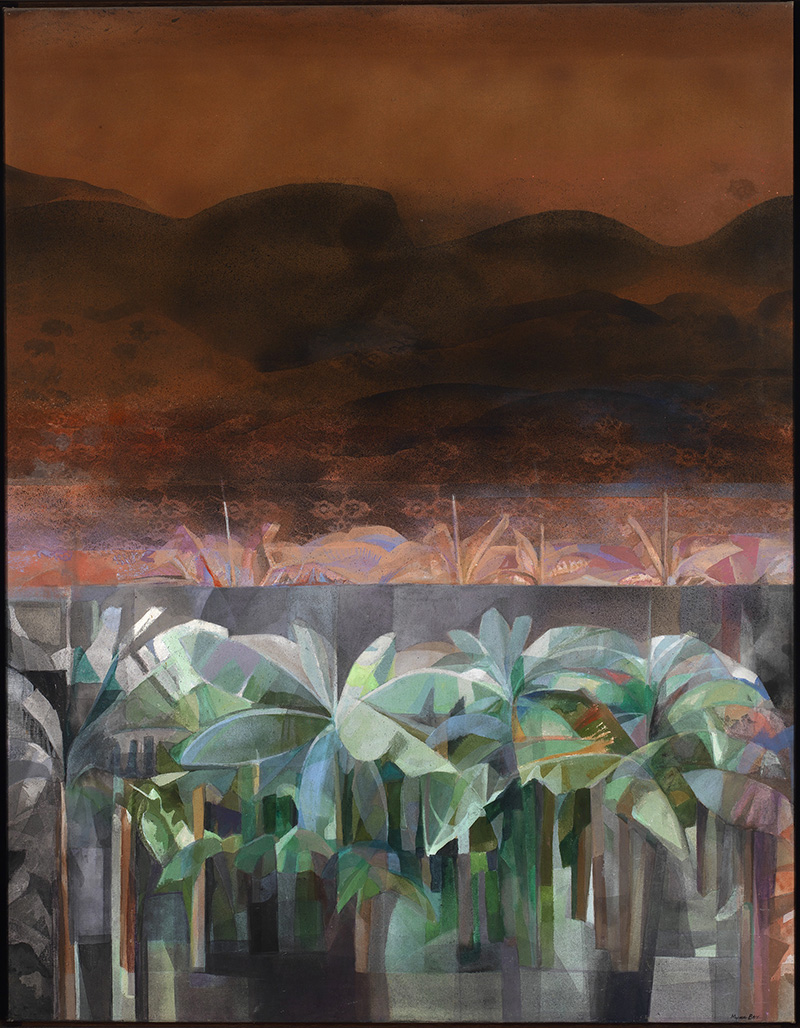

Statue of Liberty, by Gregorio Marzan, 1989. [Smithsonian American Art Museum]

In the closing moments of the Super Bowl LX halftime show, Bad Bunny marched down the field naming more than 20 countries that comprise a broader, hemispheric American identity. Holding a football inscribed with “Together, we are America,” and shadowed by a screen reading, the only thing more powerful than hate is love, the message and stakes of the show were clear: America, as an identity and a community, need not be confined to the zero-sum politics of nationalism and the nation-state system. A more powerful and capacious understanding of “American” identity emerges when we focus on the shared cultural and political possibilities of our hemispheric community.

While Bad Bunny’s performance has resurfaced these points of conversation, the message is part of a broader tradition of hemispheric politics that has been sidelined by narratives that position the nation-state as the natural conclusion of revolutionary politics. But in the early 19th century — a period known as the Age of Revolutions — people across the hemisphere regularly spoke of their American identities as a way to center the political and cultural possibilities of the “new world.” These narratives of American emancipation and innovation in turn unified popular movements by signaling that they shared an investment in resisting the authority of colonial European powers. It was precisely these hemispheric conceptions of American identity that connected otherwise disparate movements conventionally understood today as revolutions for national independence.

While independence was certainly at stake for American movements, that outcome was not always the primary, or even immediate, solution to the problem of arbitrary subjection under colonial rule. The nation-state began as a precarious solution to the problem of empire, only eventually evolving into the system of global order that we continue to negotiate today. The contingency of this outcome could be seen on display in Bad Bunny’s performance, with the show-ending procession of national flags punctuating the artist’s larger message of hemispheric unity, and highlighting the way shared identities, experiences, and investments can be mobilized to subvert the legitimacy of imperial power as a form of de facto rule.

Sidelining national narratives can prove fruitful for understanding the politics, cultures, and visions of the future that emerged from the hemispheric valences of American identity. These hemispheric conversations began in the 18th century as people across the continent questioned the legitimacy of European rule. As soon as revolutionary movements began to emerge, so did the language of a characteristically American project of emancipation, vengeance, and redemption. Here one might think of the hemispheric resonances of the 1776 United States Declaration of Independence (to begin with the event that “opens” the revolutionary period) which, as historian David Armitage argues, partially set the parameters for Americans to demand their own “right” to natural rights. The well-known claim to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness” itself marked a hemispheric break from a colonial order that treated Americans — that is, Indigenous nations, Mestizos, enslaved peoples, Creoles, and others — as subject to the prerogatives of empire in different ways.

The language of American belonging, emancipation, and governance would become fundamental to the declarations that historically marginalized groups made on the colonial state. As the “Age of Andean Insurrection” took hold, it was Indigenous leaders like Tupac Amaru who deployed the category of “americanos naturales” [natural Americans] in his Relación Historica (1780) to assert that it was the descendants of Inca nobility who held the strongest claim to legitimate rule in the region — not Europeans or elite Creoles. About ten years later, in Haiti, as revolution mounted and chattel slavery fell, so arose calls for the salvation of America. Haitian revolutionaries, in their critique of the hypocrisies of the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789), centered abolition as a facet of American politics. As Jean-Jacques Dessalines, one of the leaders of the Haitian Revolution, famously wrote in “Liberty or Death” (1804): “Yes, I have saved my country; I have avenged America.”

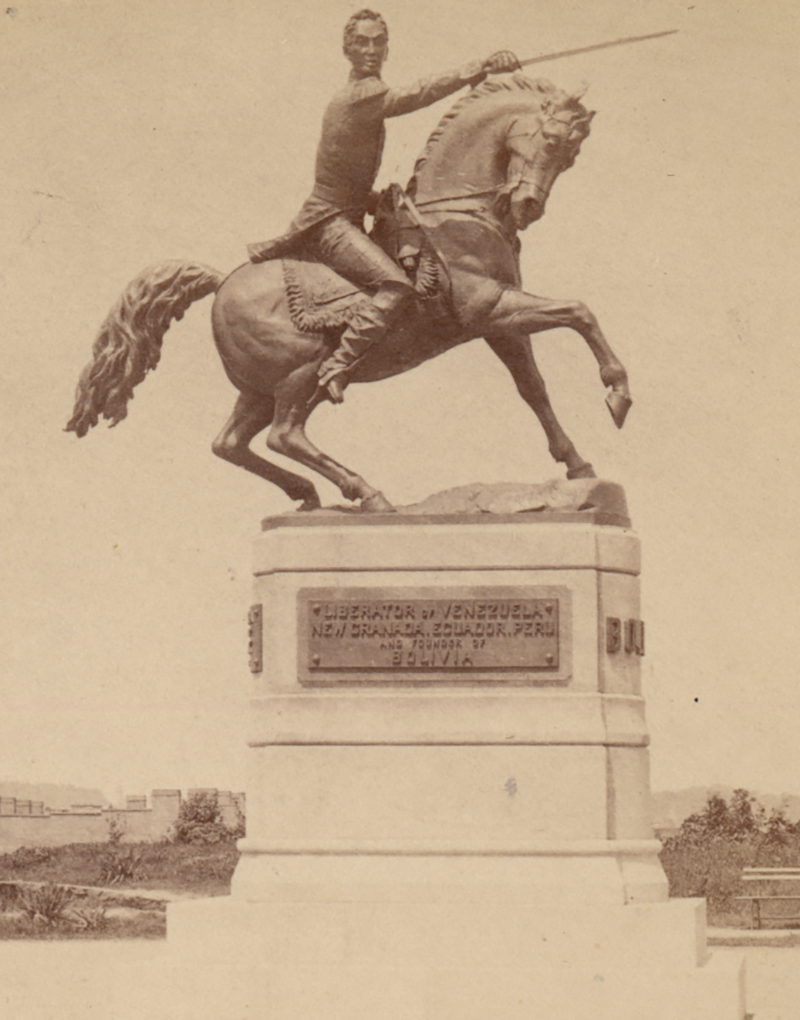

The efforts in Haiti would in turn inspire movements in the Spanish Caribbean. In La Guaira, New Granada (current-day Venezuela), Black, Mestizo, Creole, and Indigenous actors organized to reject Spanish rule and distribute their own pamphlet, titled “The Rights of Man and of Citizen with Various Republican Maxims and a Preliminary Proclamations Directed to the Americans” (1797). These hemispheric connections, however, went far beyond rhetorical commiseration. The documents distributed in the “Guaira conspiracy” were printed in Saint Domingue with aid from Haitian revolutionaries, who would later support the independence project led by Simón Bolívar.

Hemispheric American politics informed constitutional design during the independence period. The first constitution of Mexico, codified in 1814, granted citizenship to all Americans, either born or allied, with the goals of emancipating the “new world” from colonial rule. While this vision for independent Mexico was ultimately suppressed by both the Spanish and Creole elites, it is worth recognizing that leaders like José Maria Morelos viewed independence as a project that was necessarily supported by a broader, hemispheric community. Similar politics were at play in current-day Argentina, Bolivia, and Paraguay when the “United Provinces of South America” declared independence in the early 19th century by drawing on the name, politics, and vision of the “United States of America.” In considering how to advocate for the legitimate authority of the provinces, leader Manuel Belgrano argued for a constitutional monarchy that would appeal to the sovereignty of the Incas as an “original” American empire (a short-lived 1816 proposal now known as the “Inca plan.”)

These events turned hemispheric American identities into a point of popular interest across the 19th-century United States. Historian Caitlin Fitz has shown that U.S. citizens celebrated the early successes of “sister” American republics through songs, celebrations, and even by naming their children after leaders like Simón Bolívar (two prominent examples being Simon Bolivar Buckner, a Confederate lieutenant general, as well as his son Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr., who later served as a U.S. Army lieutenant general during World War II). The shared investments in hemispheric emancipation also appear among documents and speeches which are more conventionally associated with aspirations for regional hegemony. The 1823 speech in which the “Monroe Doctrine” was first articulated can be fruitfully analyzed as an appeal to hemispheric unity and to the necessity for commiseration, given that the nascent republics of the Americas remained exposed to reconquest. As President James Monroe made clear, “any attempt [by European powers] to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere (my emphasis) as dangerous to our peace and safety.” While the text is usually approached as a claim of regional authority, the language of American fraternity found throughout the speech is central to the argument Monroe develops. It was no accident, for example, that Monroe closed the speech by appealing to the “peace and happiness” of the “southern brethren” of the Americas. This rhetoric was echoed in efforts to “institutionalize” hemispheric bonds such as the 1826 Panama Congress envisioned by Bolívar, which ultimately failed to unify competing national interests across the Latin American republics or garner support from the United States.

Hemispheric attachments would recede with the advent of U.S. imperialism and its ambitions for global hegemony. By the late 19th century, the now-familiar idea of the U.S. as one “America” vis-a-vis the “rest” of the “Americas” was lucidly formulated by one of Cuba’s foundational figures, José Martí. His famous 1891 essay, “Nuestra America” [Our America], characterizes the fall of hemispheric commiseration as a matter of nationalist momentum and the allure of imagined communities, to use scholar Benedict Anderson’s term. As he writes:

For what other patria can a man take greater pride in than our long-suffering republics of America? … The haughty man imagines that because he wields a quick pen and coins vivid phrases the earth was made to be his pedestal; he accuses his native republic of hopeless incapacity because its virgin jungles don’t offer him scope for parading about the world like a bigwig, driving Persian ponies and spilling champagne as he goes. The incapacity lies not in the nascent country, which demands forms appropriate to itself and a grandeur that is useful to it, but in those who wish to govern unique populaces, singularly and violently composed, (my emphasis) by laws inherited from four centuries of free practice in the United States and nineteen centuries of monarchy in France.

The turn toward national idiosyncrasy described by Martí, while perhaps necessary and motivated by the advent of empire-building in the United States, marked a turn away from the hemispheric bonds that motivated anticolonial emancipation in the first place. Losing sight of the importance of hemispheric discourses in the break from empire, however, risks overstating the status of the nation-state system as a necessary outcome of the American revolutionary period. It is more fruitful to recognize that the break from empire motivated the rise of shared American identities, and thus that it was the return to empire which eventually led to them being forgotten.

The Super Bowl halftime show illustrated how discourses of shared American identities can be mobilized in response to the politics of empire, stratification, and erasure. Take, for example, the choreography referencing the electrical outages experienced by many Puerto Ricans as a result of material and structural marginalization under United States rule. This was equally apparent in the prominent use of a sugarcane plantation — a defining space for the economic, political, and cultural histories of the Caribbean — as the primary scene and environment of the performance. Here the case of Puerto Rico signals the living legacies of colonial rule in the Americas. As an “unincorporated territory” of the United States, Puerto Rico’s status resembles that of a contemporary colony under imperial rule — the island lacks voting representation, is economically dependent on the prerogative of U.S. institutions, and is thus subject to the prerogative of foreign officials. Thus, for many Puerto Ricans, Bad Bunny included, colonial rule remains a matter of lived experience.

Even as it drew attention to the particularities of life under colonial rule, the halftime show also pointed to the diasporic dimensions of American identities. The appearance of bodegas, street vendors, people playing dominos, and street parties throughout the performance simultaneously conjured Caribbean communities in the north and the places that their residents have left behind. These diasporic dynamics point to the broader legacy of hemispheric commiseration in the Americas. Since the early 19th century, cities like New York, Philadelphia, San Antonio, New Orleans, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, among many others, have operated as centers for political and cultural innovations that reached across the Americas. In this regard, it is fitting that the halftime show took place in one of these diasporic centers and resurfaced conversations on the who, what, and where of the American tradition.

At a moment in which many across the United States remain dangerously divided over the meaning of “America” and “American,” Bad Bunny interjected with a message that centered both unity and critical reflection — but hemispheric history, too. It is a message that is all too often obscured by national monuments, foundational myths, and narratives on independence: We are all America.