War Stories Without the History

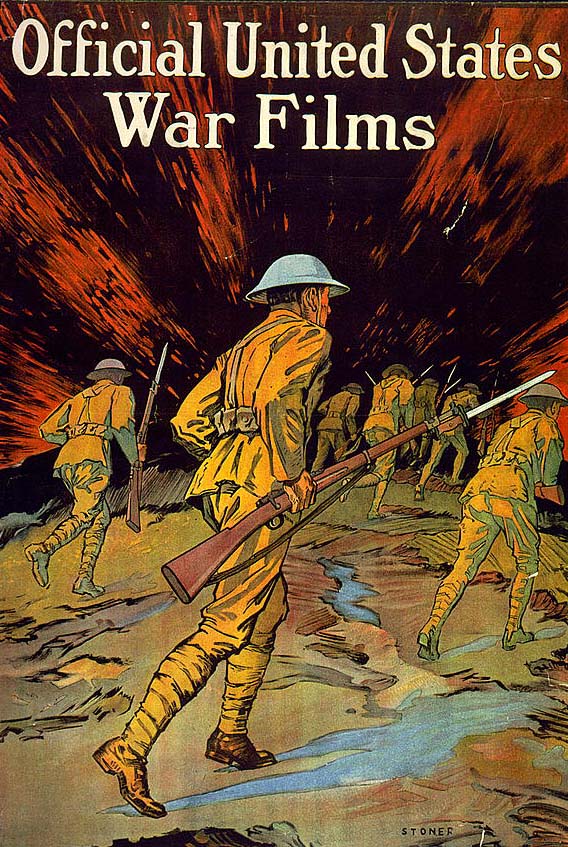

Movie poster for Warfare, 2025.

Are war films ever true? The historian Norman Kagan introduced this question in his 1974 book The War Film, adding, “true to what?” Are they true to the experience of war? Are they true to history, to facts, to contexts? Are they true to their time? In a 2012 article in the Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society about the propagandistic nature of Hollywood’s War on Terror films, scholar Tim Blackmore argues that many tell a “partial history” whereby “the attempt to make a film that has no visible politics creates a weightless, value-free historical environment where things just happen because they do, where wars are out of our control, and where obedience to an authority that must know better is the rule.”

Alex Garland’s recent film Warfare, co-written and co-directed by Iraq war veteran Ray Mendoza, is a quintessential example of the “partial histories” that Hollywood has generated about that war. Its release is cause for a critical evaluation of this corpus and its preference for the aesthetics of historical accuracy over the historical work of interpretation — and its reliance on ignoring the significance of politics in any engagement with the past.

Warfare is based on Mendoza’s experience in Iraq as a Navy SEAL in 2006, and, further, on actual testimonies by soldiers from his platoon. It plays out largely in real time as the platoon commandeers an Iraqi family’s home during the Battle of Ramadi. All of this is intended to give the project a veneer of authenticity and verisimilitude as the audience is immersed in the chaos, violence, pain, and even absurdity of the conflict.

One significant side effect of this approach is how easy it becomes to forget about why these soldiers are doing what they’re doing, or what it all might mean. The only takeaway by the end, as the platoon makes a bad situation worse and has nothing to show for it, is that this outcome is reflective of the invasion itself.

Even this belies the true nature of the project. As the film says at the start, Warfare is about re-enacting memory, not history. The memories of these soldiers, and Mendoza in particular, are re-processed through their own minds over time, then processed again via the eye of the camera and presented to us, playacting like a primary source on what occurred. Coming from a participant who is chiefly interested in having their memory actualized, there is little if any interest in analytical reflection. Sound and fury represented authentically, yet nevertheless signifying nothing.

As historian J.M. Winter argues in his 2006 book Remembering War, we ought to remember Walter Benjamin’s comment that “memory is not an instrument for exploring the past but its theatre.” Winter adds:

Understanding the power of film to serve as a mediator of prior and current memories helps us appreciate the dangers of analyzing film as if it were a transparent and unproblematic device for the construction of acceptable narratives about the past.

E.H. Carr, a British historian and diplomat, described history as “a continuous process of interaction between the historian and his facts, an unending dialogue between the present and the past.” A war film doesn’t need to look like a peer-reviewed historical account to be history, but a memory alone is something else altogether. As Winter puts it, “history is about questions, hypotheses, speculations. The traces of memory help establish their validity, but in and of themselves memories do not create history.” Memory and history inherently overlap, and to privilege one over the other without addressing any of those questions, hypotheses, or speculations is little more than an empty exercise in style. History must be interpretive, and interpretation is inherently political. Warfare and the Iraq War films that preceded it seem to be deliberately non-interpretive, and therefore beyond the reach of history.

American war films have long treasured an aesthetic of veracity — depicting historical battles with actors who have undergone real military training under the supervision of real veterans. This doesn’t mean we must necessarily say, as Francois Truffaut (perhaps apocryphally) did, that there can be no such thing as an antiwar film because representation inherently romanticizes. It does, however, mean that relying on aesthetics of accuracy cannot be conflated with proper history. Interpretation is a bad word to war filmmakers in America because it inevitably invites political scrutiny, as it recognizes how history is inherently subjective through its analytical eye. It is easier to settle for an aesthetic “truthiness” over an historical interpretation. This is a bastardized fetishization of “history” as an aesthetic category. Iraq war films are prime offenders, because they’ve had no incentive to interpret the war up to this point. Warfare is now streaming, and we are watching as the U.S. threatens to find itself in another Iraq. It is no filmmaker’s responsibility to teach the audience history. These are intended to be products of entertainment. But it remains worthwhile to notice how ignoring interpretation reverberates through time as we risk repeating the mistakes of the past.

In the years following the U.S. invasion of Iraq, Hollywood quickly realized that the safest way to engage with the war was through the plight of veterans dealing with post-traumatic stress, the re-adjustment to civilian life, and the weaknesses of veteran care. In this basic model, a veteran is haunted by flashbacks from the front while having trouble fitting back into civilian life and/or receiving veteran care. These films are usually tightly focused on the protagonist’s personal journey, and the larger context of the war is almost beside the point. If there is a political message in these films, it is that America fails its veterans. Examples include Stop-Loss (2008), The Lucky Ones (2008), American Sniper (2014), Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk (2016), Thank You for Your Service (2017), Megan Leavey (2017), and Cherry (2021).

One of the earliest — and most egregiously apolitical — examples is Home of the Brave (2006), which tells the story of four veteran soldiers returning to civilian life, and in which, for instance, one character references a History Channel special on World War II about plaques honoring American soldiers who liberated occupied French towns during that war. He wonders, “what if 10, 15 years from now we go back, do you think they’ll have statues thanking us? Because we saved ’em, we liberated ’em.” There is something tongue-in-cheek about the moment, as its absurdity seems clear even to him as he says it, but the film is certainly, according to Kagan’s guidelines, true to its time. Samuel L. Jackson’s veteran character’s son pushes him on how the invasion was really about oil and not about building a country, and Jackson’s character sputters, “You don’t know what the fuck you’re talking about, you should read a history book.” This is, perhaps paradoxically, an interesting point: depending on the perspective of the imaginary book’s author or publisher, would the war be described there in all its truth, including the son’s point of view? Can any war be fully comprehensible through a historical account?

Hollywood’s other model for representing the Iraq War — exemplified by Warfare — zooms in on life “in the shit.” In these films, anchored with veteran screenwriters or consultants, the viewer is embedded into a single mission, amplified with “authentic” details, for the duration of the runtime. Iraq is often simplified into “Middle Eastern” signifiers (music, the orange-green color filter overlaid on everything, sand), and the context of the invasion itself is not particularly relevant. Any specificity is generally elided in favor of the chaotic and messy conflict at hand. If there is a political message in these films, it is that the troops were doing their best within a complicated, nuanced, and bewildering geopolitical moment during an invasion that may or may not have been a mistake. Other examples of the form include The Wall (2017), Green Zone (2010), and The Hurt Locker (2009).

The blunt eponymous metaphor of Fernando Coimbra’s Sand Castle (2017), another version of the “in the shit” approach, imagines Iraq as a sandcastle that is built up only to be torn down again in perpetuity. Written by an Iraq War veteran, the film follows a squad tasked with repairing an Iraqi village’s broken water system, which the U.S. Army itself destroyed. After several instances of attack and sabotage, eventually one of the Iraqi laborers hired to assist suicide bombs their work, making it all for naught. The squad’s translator is the one who informs the American soldiers of the country’s history, and that “the Sunnis and the Shiites, they will always find a reason to kill each other.” Therefore, the film implies, the American efforts are moot, and the war’s destruction would have occurred with or without their interference — ignoring, of course, that it was the Americans who destroyed the system in the first place. None of the other films listed above offer anything even close to this basic, somewhat warped level of historical grounding.

Of course, film generally privileges, for better or worse, personal experience and biographical detail when engaging with history, but cinematic storytelling can be many things at once. An instructive example is Clint Eastwood’s diptych of Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima (both 2006), the former depicting an American viewpoint on the Battle of Iwo Jima and the latter, a Japanese viewpoint of the same. Coming 60 years after the historical event itself, the films not only offer two sides of the same battle, but also, as critic Jonathan Rosenbaum has pointed out, use history to implicitly reflect on what was unfolding in 2006. “One could argue that the struggle in World War II was meaningful and the occupation of Iraq senseless,” Rosenbaum writes, but even this distinction is a “civilian luxury.” The films show how dedication to one’s country is equated with a death drive that runs on symbols and myths, which are fundamentally unreal yet hold meaning. This is a moral and indeed political lesson in history, as it is re-interpreted and given renewed relevance to the contemporary audience. This is the interpretive power of history. As it turned out a little more than a decade later, Eastwood’s own Iraq film, American Sniper (2014), lacked that very same critical eye.

What about making sense of history as it happens? Stacey Peebles, author of the 2024 book The War Comes with You: Enduring War in Life, Fiction, and Fantasy, points out that the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq were broadcast around the world, sometimes directly from the soldiers themselves, with digital cameras and then smartphones in hand: “The image of combat — real combat, complete with real blood and real casualties — could be seen by others in a way that was direct, unfiltered, and undiluted by the influence of institutions or other interested parties.”

A number of Hollywood films have taken up this “digital vérité” style of cinematography — often handheld and shaky — to heighten the authenticity of their stories, recalling similar styles of realism “amid the rubble” following World War II. Many audiences tend to associate what the camera shows them with some idea of reality, which further limits any ability to answer the question of whether war films are true. At the same time, viewers also bring an inherent knowledge that the camera can lie, putting us into a contradictory position as subjective decoders of an object that pretends to be objective even as we understand this to be an illusion.

Brian De Palma’s Redacted (2007) is something of an outlier within this model for daring to show what was deemed inappropriate or incomprehensible while the war was ongoing. The film begins with the text that it “visually documents imagined events before, during and after a 2006 rape and murder in Samarra,” a real-life event. It goes on to combine “amateur” video diary footage taken by a soldier who hopes to turn what he captures into a submission for film school, alongside faux-news footage by a French documentary crew, fake internet surveillance, and video chats.

Early in the film, the videographer who intends to go to film school insists, “this camera, it never lies” — parroting the idea framing most Iraq War films’ attempt to portray the conflict. Another soldier retorts, “dude, that is bullshit, that’s all that camera ever does.” De Palma seems to be inserting himself in the story here, for his career is notorious for its playful, sophisticated, and even garish perspective on the power of images to deceive and manipulate; as he said in a 2016 interview, “I always said that film lies 24 times a second. That’s the antithesis of what Jean-Luc Godard said, that it’s truth 24 per second. That’s nonsense! Film lies all of the time.”

The fascinating tension of Redacted is his intention to “tell the truth” about the war through the artificiality of these various video formats. Digital vérité is a strategy used here to question the images we see, or don’t see, in the media, especially at a time when everything is mediated. Later on, a soldier claims, rather didactically, “you don’t see the My Lai massacre in movies, because the truth of that fascist orgy is just too hellish for even liberal Hollywood to cop to.” De Palma makes his intentions clear, pushing the film’s audience to challenge popular media narratives of the war. The extent to which he was or was not successful remains an open question: in the U.S. the film grossed only $65,388 against a budget of $5 million, and today, Redacted carries a 45% rating among audiences on Rotten Tomatoes.

De Palma, it seems, was far too early in trying to upend Americans’ memories of the Iraq War and its meaning. The war needs to spend more time becoming history, perhaps, for others to take on the same risk.

Which returns us to the question of whether a war film can ever be true at all. If cinema is, as De Palma argues, lying at 24 times a second, it might turn out to be the ideal medium for questions, hypotheses, and speculation about the past, enabling us to achieve greater understanding not through the vacuum of memory but rather the more constructive — and ultimately more political — interpretive power of history.