The Border and the Contingent Status of Mexican Workers

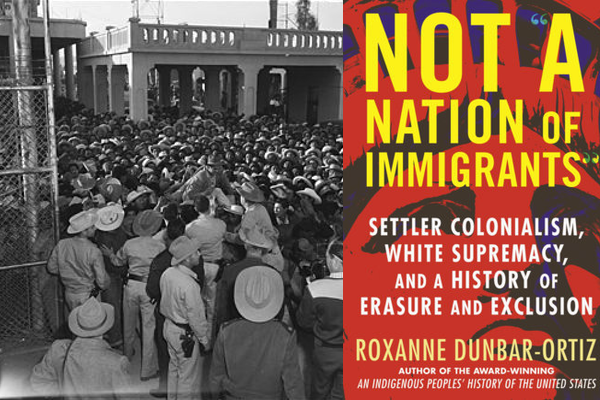

Mexican workers await entry to the US under the Bracero program, Mexicali, Mex., 1954. Photo Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive, UCLA Libraries (public domain).

Cover image courtesy Beacon Press, 2021.

THE CONTINGENT STATUS OF MEXICAN WORKERS

The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act was the first federal immigration law, marking the first time that a particular group was designated as “illegal.” Because of the exclusion, many Chinese immigrants entered the US through México, so the US further tightened restrictions at the border. The second law was the Immigration Act of 1917, extending exclusion to all Asians. That law targeting Asians also required an eight-dollar-per-person fee and a literacy test to enter the United States. The impact was immediate, reducing the number of legal immigrants at the border from 295,000 in 1917 to 111,000 in 1918. The draconian 1924 Johnson-Reed National Origins Act limited the number of immigrants allowed entry into the United States through a national origins quota that provided visas to 2 percent of the total number of people of each nationality in the United States as of the 1890 national census. The total number of immigrants allowed entry under the law was 165,000. The total number admitted in 1924 was 162,000, of which 141,000 were from Northern and Western Europe.

There were only 78,000 Mexicans counted in the 1890 US census, but the restrictive quotas did not apply, because a quota exception was made for workers from Western Hemisphere countries, which meant México, as immigration from the other Latin American countries was minimal. This exemption resulted from the political power of the business interests in the western states. The agricultural and mining industries were dependent on Mexican labor, which they preferred precisely because of the absence of the workers’ bargaining power at the height of US labor wars. The Mexican workers, supporting large extended families and communities in México, worked cheap and withstood harsh working conditions to keep their jobs. Following the Mexican Revolution with the reform government in power, Mexican authorities attempted to persuade people to stay and work to rebuild war-torn México, but in reality, there were few jobs in México. The 1917 Mexican constitution guaranteed free movement but required work contracts in order to emigrate legally, which were nearly impossible to obtain, so the migrants’ exit was usually undocumented, as was their entry into the United States, making them vulnerable to exploitation.

The 1924 immigration law also created the US Border Patrol, housed in the Department of Labor, clearly targeting those crossing the US-México border, at the time seeking to bar the entrance of Chinese. Between 1900 and 1930, some seven hundred thousand Mexican migrants entered the US legally, while many others entered without documents. Most migrants worked seasonally and returned to their villages in México, which growers encouraged. As one California grower put it, after harvest “I will kick them out.” And that is exactly what happened on a large scale beginning in 1930. Agribusiness employers in the Southwest preferred Mexican seasonal migrant workers, because at the end of harvest, the workers were on their own, without pay or housing during the winter season. The migrants who chose to stay would relocate to cities where charities or local governments would provide relief during the periods there was no work. This shifted the expenses from employers to the public, which caused resentment, mostly toward the workers. But the caregivers also complained about the employers. The Colorado Catholic Charities director queried, “Why the citizens at large, the Community Chest, the churches, the tax-payers, should have to care for the employees of the sugar companies, the railroads, and mines, between seasons of labor, is not clear to the students of economics or justice.” This situation was dubbed the “Mexican problem,” which came to encompass other racial resentments against Mexicans.

One aspect of Anglo racism in the Southwest was not wanting their children to go to school with Mexican children. By 1928, segregation of Mexican American children in schools was widespread in California and Texas. In eight California counties, enrollment in sixty-four schools was 90 to 100 percent Mexican American, and in Texas, school boards created forty separate Mexican American schools. In 1930 in the San Diego County town of Lemon Grove, the local school board attempted to construct a segregated school for seventy-five Mexican and Mexican American elementary school children. The Mexican parents organized and took the school board to court and won. The Superior Court of San Diego County ruled that the move violated California state laws because ethnic Mexicans were considered white under the state’s Education Code.

This decision is often hailed as the first successful desegregation decision in the United States, preceding the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the hallmark US Supreme Court decision ordering desegregation of all public schools. However, the Lemon Grove decision validated the US racial code that recognized only three “races”: Black, white, and yellow. The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had guaranteed to Mexicans who remained within the United States after the new border was established “all the rights of citizens of the United States,” including the right to vote, hold public office, own land, and testify in court—all the rights of white people. Elite former Mexican citizens were able to enter the Anglo social order. But many of those who were poor or owned little or no property, or who lived in socially segregated barrios, were sometimes classified by federal or state officials as Indian and denied white rights. Yet there was no consistency or institutionalization of Mexicans racially; depending on the place and time, Mexicans were treated as white according to status and skin color.

The federal Census Bureau classified Mexicans as white up to 1930, when it responded to congressional pressure and started enumerating Mexicans as a separate racial group, “Mex,” along with “Negro,” “Indian,” “Chinese,” and “Japanese.” Outside the Southern states, intermarriage was not illegal but often stigmatized. In many parts of the Midwest and even more in the Southwest, “Whites Only” signs barred Mexicans from public places such as theaters, dance halls, parks, swimming pools, beaches, beauty parlors and barber shops, bowling alleys, restaurants, and even cemeteries. Voter intimidation and workplace discrimination were common. None of these restrictions were sanctioned by law, as was the case for Black people under Jim Crow regimes. But in the Southwest, especially Texas, courts upheld the boundaries more often than they challenged them. The Lemon Grove case was isolated as a local event and set no precedent affecting California or elsewhere; segregation of Mexican and Mexican American children continued in some places to the 1970s. While the Lemon Grove case was in process, forced “repatriation” of Mexicans and Mexican Americans was in full swing.

Excerpted from Not "A Nation of Immigrants," by permission of Beacon Press, c. 2021.