Discarding Legal Precedent to Control Women's Reproductive Rights is Rooted in Colonial Slavery

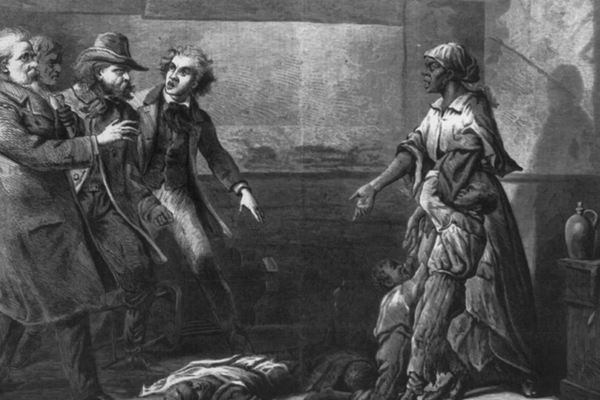

The Modern Medea (1867) depicts Margaret Garner, who, having escaped slavery, was accused in 1856 of murdering her daughter to spare her being returned to bondage.

The incident reflects the consequences of the American colonial legal innovation of partus sequitur ventrem discussed by the author.

Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito made reference to the 13th century legal opinions of English jurist Henry de Bracton in his leaked draft opinion foreshadowing the court overturning Roe v. Wade. De Bracton was an ancient misogynist who believed women to be inferior to men, and that they sometimes actually gave birth to monsters. Alito also cited the 17th century English jurist Sir Matthew Hale, who sentenced women to death for witchcraft and did not believe marital rape possible because women were the property of men. These antiquated views are vile. That a 21st century Supreme Court justice would cite these men, repugnant. But American jurisprudence has long cherry-picked opinions from the English law upon which it was founded to suit the needs of the wealthy and powerful it serves, and women’s bodies have long been a fulcrum for determining which legal opinions to pick.

Key v. Mottrom, the 1656 case which came before the colonial-era Virginia Supreme Court, shows the extent to which American jurisprudence will torture English law to arrive at opinions favored by those in power. As in the case of abortion before today’s court, the stakes in the Key case could not have been higher, for they involved who would, and who would not, be considered a slave at birth. Thus, a case from the 17th century and a case four centuries later share in common that both are at the nexus of gender, class and race.

Elizabeth Key, born circa 1630, was the daughter of one of the first African women brought captive to Virginia in the 1620s, and an Englishman named Thomas Key, who arrived in Virginia in 1619. Key soon married an aristocratic woman named Martha and thereby ascended the ranks of colonial American power and wealth. Thomas Key died in 1636, but not before signing a document transferring young Elizabeth to the custody of one Humphrey Higginson, who sold her to William Mottrom. Upon Mottrom’s death, the executors of his estate sought to resell Elizabeth as property. Only this time she objected, suing Mottrom’s executors for her freedom, and that of her young infant son, John.

Key’s case was first heard in the Northumberland County Court, which ruled in her favor. But, on appeal she received an adverse ruling from the Virginia Appellate Court, thus setting up a showdown at the Virginia General Assembly, the colonial-era Supreme Court. In colonial America, there was no separation between the judiciary and the legislative branches of government; legislators were justices, and justices were legislators. Key pleaded she was not Mottrom’s property because under prevailing English law she was not a slave. Bondage or freedom, following English custom and law at the time, was based on the status (bound or free) of the father, not the mother. On that basis, the colonial Supreme Court issued an opinion (not a ruling) in Key’s favor and sent the case back to the lower Northumberland County Court for final disposition in 1659. Mottrom’s executors, probably sensing they would lose on appeal, offered no objections to the original ruling, so Elizabeth and her son were set free.

Other than genealogists tracing actor Johnny Depp’s ancestry to Elizabeth Key, her case would probably have remained an interesting footnote in American jurisprudence history were it not for the fact that colonial legislators and jurists realized that her victory opened an absolutely huge loophole in the legal underpinnings of slavery. Most interracial coupling during the early years of this country occurred when White men, forcibly or otherwise, had sex with Black women. If the children of those liaisons were by law free, then the foundations of slavery in America were set to crumble.

So legislators, who were also the colonial era jurists, swung into action following the Key verdict, much like legislators in conservative states swung into action following the original ruling in Roe v. Wade. The rallying cry then was that the legal theory of partus sequitur patrem (the status of the offspring follows the father) had to be overturned for slavery to survive and to thrive in America. In the late 1600s, in Virginia and Maryland, a new legal theory partus sequitur ventrem (the status of the offspring follows the womb) took the place of the old English law, and statues were enacted and enforced to that effect. Not Gettysburg nor Antietam, but the female body—the Black female body—was the original ground upon which the battle for slavery in America took place.

Colonial reaction to Elizabeth Key’s case was just the first of many instances where English law was imported, then warped, by American jurisprudence to support slavery. Black women, other women of color, and all poorer women lacking the means to travel to states where abortion will still be legal will be most beset by the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade. Alito’s leaked draft is a reminder of how the female body continues to be a battleground for matters of gender, class, and race; a battleground where powerful White men feel they have an inalienable right to rule.