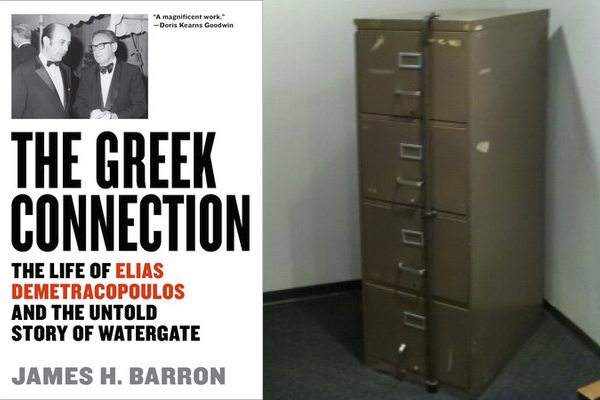

Watergate at 50: Did Kennedy Loyalists Squelch a 1968 "October Surprise" that Could Have Beaten Nixon?

It was a 1968 October Surprise story that might have changed the course of history. Imagine Hubert Humphrey taking office as President in January 1969, not Richard Nixon. We wouldn’t be at the 50th anniversary of the Watergate break-in, to name just one consequence with wide-reaching effects for American democracy.

Elias Demetracopoulos, an exiled journalist living in Washington, uncovered a scandal. After escaping the military dictatorship that had seized power in Athens the year before, he was fighting to restore democracy to his homeland. In early October 1968, Elias learned from his network that the junta was secretly funneling cash to the Nixon-Agnew campaign—millions in today’s dollars. The pitchman and bagman was Tom Pappas, a Greek-American tycoon and longtime GOP fundraising powerhouse. Pappas would later be described on the Watergate tapes as “the Greek bearing gifts.” The CIA’s Greek counterpart, likely using “black budget” US aid, provided the payoff.

No longer a working journalist, Elias tried unsuccessfully to get the New York Times and other papers to investigate his tips. Gloria Steinem, in New York magazine, scoffed at Elias’s charge, claiming the front-runner Nixon didn’t “need to be dishonest” to win.

With time running out, Elias turned to Humphrey’s campaign manager Larry O’Brien. On October 19, at Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate, he provided details of the Pappas gambit. He urged O’Brien to ask President Lyndon Johnson to get CIA head Richard Helms to confirm the information. Elias offered to set up meetings with his sources in Athens. He even offered to fly them to Washington to testify, but, for that, those sources would need financial help, until they could safely return home.

Timely disclosure could have changed the result of the second closest U.S. presidential election in the 20th century (Nixon’s Electoral College margin exceeded only Woodrow Wilson’s in 1916 and his popular vote margin surpassed only John F. Kennedy’s in his 1960 defeat of Nixon). O’Brien made Elias promise not to discuss the revelation publicly, because of the sensitivity of involving LBJ and the CIA. Trusting O’Brien was a fatal miscalculation.

***

In mid-October, a Gallup poll reported that 29 percent of voters were uncertain whom they’d vote for. Just before the first Demetracopoulos-O’Brien meeting, NYT columnist Eileen Shanahan noted “a widespread lack of enthusiasm for any of this year’s candidates [which] may mean a higher-than-usual possibility of last-minute switches if there is a last-minute campaign issue or disclosure.”

Nixon insiders feared they were one bad story away from losing. Given the softness of Nixon’s support, Humphrey’s media advisor Joe Napolitan begged O’Brien to go on the attack, but O’Brien directed Napolitan “not to say anything to anyone.”

Washington Post columnist David Broder observed that, if the payoff story had been released in mid-October 1968, it would have been “explosive.” The “New Nixon” myth would have evaporated, he surmised, inviting “others to come forward with similar reports, which cumulatively could have changed the outcome of such a close election.” By election day, the race was too close to call.

***

Boston Globe political insider Bob Healy learned from off-the-record CIA sources about Pappas and Agnew pressuring Greek nationals and the junta to donate generously to Nixon. Afterwards, Healy received a call from Kenny O’Donnell, former JFK appointments secretary, identifying Pappas as the key operative in this illegal fundraising scheme. Healy alerted Globe editor Tom Winship, who, sensing a big story, told reporter Christopher Lydon to “dig deep.” Pappas, in a Lydon interview, dismissed the allegations as baseless rumors. O’Brien gave Lydon the gist of what Demetracopoulos had told him, without disclosing his source, but added that the story couldn’t be corroborated. So, Lydon wrote: “Few of those original suggestions about Pappas and Agnew seem credible now,” adding that rumors “that Pappas is the conduit of campaign funds from the Greek junta to the Nixon-Agnew treasury” were “an unsubstantiable charge.”

The article was news enough for the DNC to issue a press release, blandly headlined: “O’BRIEN ASKS EXPLANATION OF NIXON-AGNEW RELATIONSHIPS WITH PAPPAS.” It had no impact on the race.

On October 26, O’Brien told Elias that his proposals were all too risky and Johnson would not ask Helms about the Greek money transfer. Well-informed Globe editor Charlie Claffey claimed Winship could have arranged the needed U.S. living expenses for Elias’s sources, but was never given the opportunity. Newly available archival information and interviews indicate O’Brien lied to Elias. He had never told Johnson, or Humphrey. But why?

***

Elias had been an aggressive reporter whose exposés earned him the label persona non grata by Greek and American governments. As a member of the Kennedy inner circle, O’Brien would have been well-aware of the fallout from Demetracopoulos’s controversial 1961 interview with Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke, which embarrassed President Kennedy and was discussed at two of JFK’s first press conferences. O’Brien, Kenny O’Donnell, and former JFK press secretary Pierre Salinger were all close, and O’Brien surely talked with them after his first meeting with Elias.

Salinger likely told O’Brien about Elias’s infamous intelligence dossier, filled with misinformation and blatant lies claiming Elias was both untrustworthy and a Communist spy. It is probably no coincidence that on Tuesday, October 22, three days after his first meeting with O’Brien, Elias received a call from a California friend who warned him that Salinger was again smearing him, claiming Demetracopoulos worked for “the other side.”

Kennedy advance man Jim King knew O’Brien and his father from the 1950s when they operated a Springfield, MA tavern organizing working-class Irish Democrats. King concurred with historian Robert Dallek’s description of O’Brien’s “affinity for negative thinking.” He presumed that, even in 1968, “the McCarthy that would strike deepest fears into O’Brien’s Irish Catholic heart was not Gene but Joe.” O’Brien came of age during Joe McCarthy’s witch hunts and still believed that it was a political third rail to deal with anyone tainted with a whiff of Communist connections. The disinformation campaign against Elias had been anything but subtle.

The problem O’Brien had with Demetracopoulos was not his message, but the messenger himself. It is ironic that blowback from years of baseless, inflammatory anti-Elias attacks fanned by Kennedy insiders may well have cost Humphrey the election and given the country Richard Nixon and Watergate.

NOTE: Historians later confirmed the illegal Greek money to Nixon gambit, referring to it as “a ticking time bomb,” exposure of which “caused the most anxiety for the longest period of time for the Nixon Administration.” There is strong circumstantial evidence that the information Elias gave O’Brien at the Watergate in 1968 was part of what the burglars were looking for in 1972.