Climate Change Just Erased the Past in Kentucky. Where Will it Happen Next?

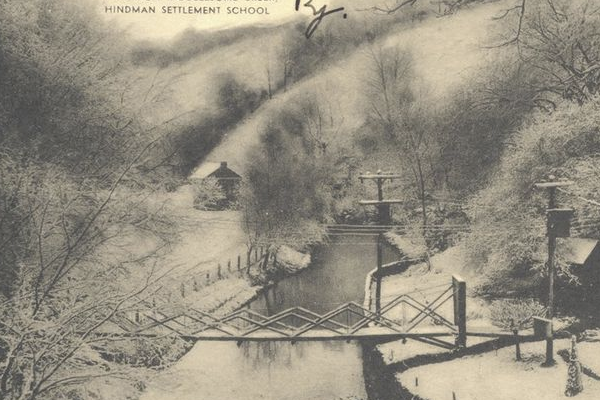

The Grounds of the Hindman Settlement School and Troublesome Creek, Knott County, KY, ca. 1950

In the early morning hours of Thursday, July 28, the rising floodwaters of Troublesome Creek in Knott County, Kentucky breached the Hindman Settlement School’s archive. In less than fifteen minutes, the small room– which housed hand-made dulcimers, hundred-year-old diaries, letters to and from early workers at the school, and hundreds of photographs, account ledgers, family Bibles, and rare newspapers, among other historical artifacts– was filled with muddy water and sludge. Hindman staff did the best they could to stop the floodwaters, but this was an impossible task. What happened to the wife of an employee, who fell and broke her leg in the process of trying to escape the rising waters– attests to this, as does the horrific news of a family who lost all four of their young children to the deluge.

As a historian who has spent weeks in this archive– a critical source of information for my forthcoming book– I know what was damaged in this flood better than most. I could tell you about the rare newspapers I found that have helped me piece together a narrative that challenges stereotypes about the region as unlettered and ignorant. I could tell you about the diaries of northeastern college women who came to Appalachia at the turn of the century to work at the Hindman settlement school, founded in 1902. (Some of them allowed their experience to change them– to shift their preconceived ideas about the people with whom they worked– and others did not.) I could tell you about hundreds of photographs: of people, railroad trestles, coal tipples, and landscapes devoid of trees due to overlogging; photographs of hundreds gathered at the edge of a creek for a Baptism, or gathered at the top of a mountain for the funeral of a little baby.

I could go on and on. Any historian or archivist knows what a treasure these small pieces of the past are. And I want to think people who are not trained in this manner do too. But we must wake up to the fact that irreplaceable pieces of history have been lost forever. Volunteers acted as quickly as they could in the aftermath of the flood to salvage what they could, but even if they are successful in saving some of the materials that were sent last night to Eastern Tennessee State University’s Archives of Appalachia for cleaning and conservation, there are hundreds of other pieces of the past that have been lost forever. We need to stop saying “We could lose history” and admit that we have already lost it.

We will keep losing important pieces of the past if we do not take climate change seriously. While it is undeniable that more preventative work could have been done to protect Hindman’s archive from flood waters, it is also true that places like Knott County are increasingly at risk of climate emergencies due to warming temperatures. Climate change is making flooding worse, and a disproportionate share of that flooding is expected to affect Appalachia. Located in one of the poorest regions in the country, institutions like Hindman simply do not have the financial resources to protect their materials from these kinds of natural disasters. Even regional art and cultural centers that are better known, like Appalshop in Whitesburg, Kentucky, cannot escape this reality. They too were hit by fast-rising flood waters, and suffered substantial losses to their collections of more than 20,000 items. Many of those were sound and film recordings of several decades, including materials deposited by Harlan County’s Pine Mountain Settlement School for safe keeping.

Outside support for flood victims has been swift. The area desperately needs it; as Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear (D) has explained, it will take years for small towns like Hindman and Whitesburg to rebuild. That process will be an uphill battle to say the least, especially for those families who have lost everything– loved ones, cars, homes, savings, personal belongings– in the flood.

But we have all lost something in this flood, and we would be well served to remember that. It is easy to dismiss climate change when it is happening in someone else’s county. It is relatively easy to send money or cleaning supplies to ease their pain. And it is impossible to get back the pieces of the past that washed away in these waters. Those pieces of history belong to all of us and tell us a story about America’s history writ large. Appalachian history is America’s history, even if contemporary perceptions often cloud our interpretation and lead us to regionalized and racialized assessments of “us” and “them.”

So, what do we do now? Beyond the obvious and frustratingly oft-repeated urgings to call legislators, I would like to see people who are invested in preserving the past put their money toward digitization efforts in these small locations. Every historian can tell you that some of their most exciting and rare finds came from remote or unlikely places– from unprocessed collections, from shoeboxes in an attic, or in a folder in a courthouse basement. As climate change and extreme weather patterns continue to affect us, we will continue to see these kinds of records vanish forever.

We cannot afford this loss, which stands to disproportionately affect the historical record of poor people and people of color. Historical analysis has traditionally overlooked those groups, especially when those categories intersect. Climate change disasters like this one will only further erase the narratives and stories these people have left behind. It is thus not too dramatic to say that inaction on climate change erases our collective past and expunges the stories of marginalized peoples with special vigor. Black Appalachian scholars and activists, like Emily Hudson, who operates the Southeast Kentucky African American Museum & Cultural Center in Hazard, Kentucky, and Dr. Enkeshi El-Amin and Angela Dennis, who host the “Black in Appalachia” podcast, are doing what they can to bring visibility to Appalachia’s African Americans. But they need funds and resources to continue that work, just as Hindman and Appalshop do. It’s time we do something about that funding, because it is almost too late.

Editor's note: The Hindman Settlement School has a fundraising page for donations specifically to support the restoration and protection of its archives. It is also raising funds to serve the great need for food, shelter and hygiene for those displaced by flooding in Eastern Kentucky.