The Secret Anglo-American Empire of Intelligence

There is a telling moment near the beginning of Citizenfour, the Oscar-winning documentary film featuring the initial interviews between NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden and reporters. Snowden sits on the edge of a hotel bed describing a collection of documents to journalists Glenn Greenwald and Ewen MacAskill. The documents, listed in a computer file directory, include material taken as part of the National Security Agency’s [NSA] global surveillance program. As Snowden talks, Greenwald and MacAskill lean forward to view the files, salivating over the potential headlines from the documents, particularly those concerning German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Snowden, however, remains distant from the excitement, offering the documents to Greenwald and MacAskill without editorializing and without pointing them toward specific stories. For Greenwald and MacAskill, it seems, the importance of Snowden’s revelations lie in the contents of the documents; for Snowden, the importance of the revelations remain the documents themselves and the information regime that made this archive available in the first place.

The most critical part of this information regime – one that Snowden mentions again and again throughout the course of Citizenfour – is the cooperation between America’s NSA and Britain’s GCHQ. He reveals that the NSA are “in love” with a GCHQ system called Tempora, which Snowden claims is responsible for collecting and processing more signals intelligence (SIGINT) than any of the NSA’s standalone programs. In addition to the amount of material provided, Tempora also shields the NSA from the potential legal attacks that the organization could encounter from similar data collection programs within the United States. Viewers of Citizenfour may be left with the impression that this sort of security cooperation between America and Britain is a recent phenomenon – one that resulted from the War on Terror. Yet Tempora is merely the most recent entry in the long history of collaborative security programs between the two countries.

This collaboration, which has existed in one form or another for almost a century, represents perhaps the deepest and most durable connection between Britain and the United States. It has lasted longer than most defensive alliances, extradition treaties and trade arrangements. It also seems to run deeper than many of the two countries’ shared cultural assumptions – with the exception of the common love for period dramas, the Beatles and Benedict Cumberbatch. The secret nature of this collaboration, however, often obscures its presence and importance from the public and from historians. Nevertheless, there is reason to see this security partnership as the sole basis for the oft-derided “special relationship.”

How do we explain the longevity and the level of commitment to this especially perverse relationship, one that trades on seemingly untradeable items of national security?

In the beginning, at least, this relationship hinged on the British desire to defend its empire against internal and external threats. Britain’s security services – including MI5, MI6 and the Metropolitan Police’s Special Branch – looked to the United States in the early years of the twentieth century for assistance in maintaining surveillance on American-based Irish Fenians and Indian nationalists, particularly the members of the Ghadar Party. During the First World War this informal cooperation reached a formal footing after America’s declaration of war against Germany – an event made possible, in part, by the release of the Zimmerman Telegram by British cryptographers. Although the context of the war provided an impetus for further security cooperation between the United States and Britain, German espionage never lived up to the perceived threat. Leaders in Washington and London took this lack of German success in the war as a sign of security excellence, rather than as an indication of German ineptitude. In this way, the First World War helped to establish the most consistent trend in counterespionage history: the fear of potential attacks is almost always more important to the health of security services than successful attacks.

Early cooperation between the two countries provided Britain with obvious benefits, but it also seemed desirable for American security officials. While the United States received little advantage from keeping tabs on Fenians and Indian nationalists, collaboration with British security services nevertheless helped various American security organizations establish institutional permanence. We are used to thinking solely of the FBI when considering American domestic security, but during the First World War and interwar periods, the FBI counted as but one among many federal and non-federal agencies competing for the exclusive right to spy on American enemies, including the State Department, the Secret Service, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics and the New York Police Department.

Work with a foreign power – particularly Britain – not only provided these agencies with access to information, but also with a greater professional profile vis-a-vis their bureaucratic competitors. It was only through a combination of utility, guile and propaganda that the initially insignificant Bureau of Investigation (BOI, renamed the FBI in 1935) emerged as the de facto security organization for the United States. J. Edgar Hoover, of course, played a large role in this process. His ceaseless promotion of FBI exploits helped to establish the organization in the minds of foreign security officials, while the FBI’s access to unparalleled identification records and seemingly advanced technology like the polygraph offered concrete reasons to pursue a partnership.

The Second World War saw the security partnership between America and Britain go from a temporary marriage of convenience to a seemingly eternal aspect of the special relationship. This process began well before the United States entered the war. Although American neutrality prevented official intelligence exchange with warring countries, Britain maintained an unofficial exchange with the United States through the offices of British Security Coordination (BSC) in Rockefeller Center beginning in 1940. Controlled by MI6, BSC served two purposes: to prevent enemy espionage and sabotage in North America and to use whatever means necessary to encourage America to enter the war.

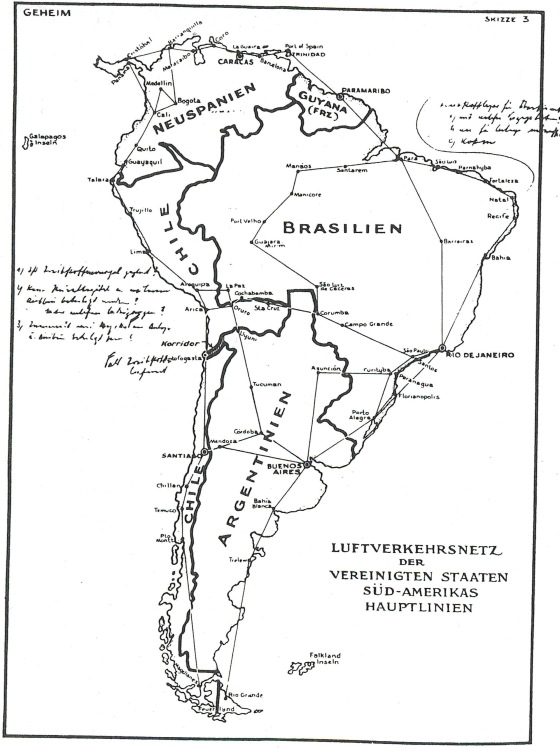

Britain accomplished these two goals thanks in large part to the work of BSC director William Stephenson, who developed a close relationship with William “Wild Bill” Donovan, head of America’s Office of Strategic Services (OSS, precursor to the CIA). Stephenson supplied Donovan, an anti-isolationist, with British intelligence on German espionage throughout North and South America. Donovan then passed this intelligence on to President Franklin Roosevelt, who made several references to this intelligence – without mentioning the source – in public speeches about the war prior to Pearl Harbor. The most famous instance came in October 1941, when Roosevelt delivered a speech that made reference to a projected map of South America under Nazi control. Unbeknownst to Donovan and Roosevelt, however, this map was not the result of legitimate British intelligence, but instead had been completely fabricated by William Stephenson.

What’s a small, policy-changing lie between close friends?

The intelligence alliance between America and Britain continued in the postwar period thanks to a shared desire to check communism. This desire coalesced into the well-known UKUSA agreement on signals intelligence in 1946. The treaty eventually embraced Britain’s old dominions, including Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The presence of the old dominions, as well as British dependencies, played a critical role in the utility of this arrangement for the United States. By the 1950s, America possessed sufficient technical ability to acquire and process Soviet transmissions, but this technical ability still required geographic proximity to communist zones of influence in order to intercept signals. The British Empire, and eventually, the Commonwealth provided that proximity as well as listening posts for other important areas of foreign policy, including the Middle East and South Asia. Moreover, the United States also appreciated the intelligence agreement in the immediate postwar period because of the continued usefulness of British cryptography, particularly the decrypts that emerged from the Ultra project. Indeed, one of the reasons why the work of Alan Turing and the other members of the wartime Enigma team remained an official secret until 1974 was because the machines were still in use by many third world countries during the early Cold War.

See the National Archives for online copies of the original UKUSA agreement and the resulting intelligence like the one above.

The UKUSA alliance (also referred to as “Five Eyes”) provides the current basis for cooperation between the NSA and GCHQ. Given the long history of this alliance, the present situation with Tempora appears to be business as usual rather than an outrageous new development. What is shocking about Snowden’s revelations is not so much the fact that this kind of cooperation exists, it is the fact that we keep being shocked that this cooperation exists. If we wish to question or, perhaps, to eliminate this cooperation, it will be useful to keep in mind the history of this alliance and the dramatic role it has played in modern history, particularly in America’s recent past. British intelligence provided a basis for American involvement in the First World War, the Second World War, the Cold War, and, most controversially, the Iraq War. Britons concerned with the development of American imperialism abroad may have their own country to blame. As William Donovan, the so-called father of American intelligence, remarked on the work of William Stephenson and BSC during the Second World War, “Stephenson [and the British] taught us all we ever knew about foreign intelligence.”[1] Citizenfour makes clear that this empire of intelligence continues to teach America.