A Reason Republicans May Not Wish to Proclaim Themselves the Party of Lincoln

The Republican Party may soon live up to its moniker, “The Party of Lincoln,” though not in a way that bodes well for the GOP. Abraham Lincoln, of course, was the first Republican president. While he is heralded today as one of our greatest chief executives, he was never very popular in his own day. Nor was his party.

It is worth remembering that the Republican Party was not a “national” party from its inception; it drew its support exclusively from the North. Born in 1854 in Jackson, Michigan, the party in its earliest days was organized around opposition to the extension of slavery into the western territories. Concern over slavery in the West erupted in the wake of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1853, which opened up those two territories to slavery after over thirty years of prohibition there. Energized over containing slavery, the party attracted anti-slavery activists, Northern Whigs, and ex-Free Soilers, who similarly wanted the West kept as “free soil for free men.”

Early Republicans knew that their fledgling party needed to broaden its appeal beyond the slavery issue. So they advocated support for internal improvements, what today we would call infrastructure. As New York Tribune editor Horace Greely wrote in 1860, “An Anti-Slavery man per se cannot be elected.” But, “a Tariff, River-and-Harbor, Pacific Railroad, Free Homestead man, may succeed although he is Anti-Slavery.” Containing the “peculiar institution” alone would not be enough to secure victory, but adding other planks to the party’s platform could result in electoral success.

For obvious reasons, the Republican Party held no appeal for southerners. During the 1860 election, Lincoln’s name did not even appear on the ballot of ten southern states. Although he was able to amass a majority of the electoral college votes, Lincoln won only 39.7% of the popular vote. Six out of every ten Americans voted for someone else, as the nation descended into civil war.

Four years later, some Republicans wanted to dump Lincoln for Salmon P. Chase or John C. Fremont. While Republicans renominated Lincoln, they replaced Hannibal Hamlin as the vice presidential nominee in favor of Andrew Johnson, a War Democrat. Republicans knew their base alone would not be enough to secure victory. The party of Lincoln had such limited appeal that Lincoln himself needed the support of Democrats to win reelection.

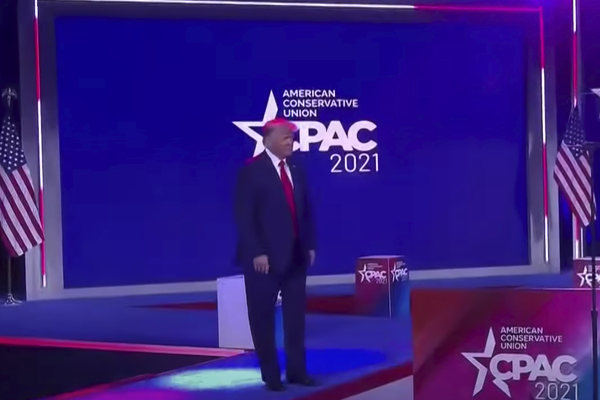

Fast-forward to the present, one hundred and sixty years later the Republican Party chances again to become a party of limited appeal. Under Donald Trump’s leadership, a deep fracture has grown within the GOP. While a majority of Republicans remain loyal to the former president, some have grown weary of his mendacious ways. Even after election results were counted and recounted, Donald Trump will not concede defeat. And as he continues to falsely claim victory, he demands that Republicans similarly proclaim “the lie.”

Even before the election, fissures in the Grand Old Party were apparent. Some Republican leaders, especially those who had or were about to retire from office, rejected Trump. It was a strange and telling moment when Ohio’s former governor John Kasich, a life-long Republican, spoke at the Democratic National Convention in support of Joe Biden’s candidacy.

Nonetheless, the influence Trump has over Republican office holders is so great, the vast majority do not dare suggest that the emperor has no clothes—that Trump lost the election fair and square. Instead, they embrace and perpetuate the lie. To do anything less will result in Trump’s wrath and a primary challenge. Even after January 6, only a small number of Republicans in Congress have shown the political will to challenge Trump’s deceit. So, they voted for acquittal again, when he stood trial for inciting the capitol riot. In their shortsighted effort to save their own political skins, those Republicans are fundamentally transforming their party.

In stark contrast to the majority of House Republicans who supported efforts to overturn the Electoral College vote, ten Republicans voted for impeachment. In the Senate, though the handful of Republicans who mustered the courage to vote to convict might seem small, they represent a growing number who reject Trumpism and the lie. Once alone, Mitt Romney was joined by Lisa Murkowski, Susan Collins, Ben Sasse, Pat Toomey, Bill Cassidy, and Richard Burr. Indicative of the depth of Republican divisions, several of them were censured by their own state party committees.

The Republican electorate is similarly split. A full three out of every four Republicans believe that there was widespread voter fraud in 2020, handing the election to Biden. Though most Republican voters remain loyal to Trump and his lie, a growing number are re-assessing their fealty, repulsed by the events of January 6. For them, there was no steal to stop. They would not believe the lie. After all, “you can’t fool all of the people all of the time.”

Such divisions within the Republican Party threaten to devastate the GOP. A party that has only won the popular vote once in the last eight presidential elections can ill afford its present fracture. Trump’s lie chances to fatally handicap the party of Honest Abe. As Lincoln warned years ago, “A house divided against itself cannot stand.”